[ 0010 ]

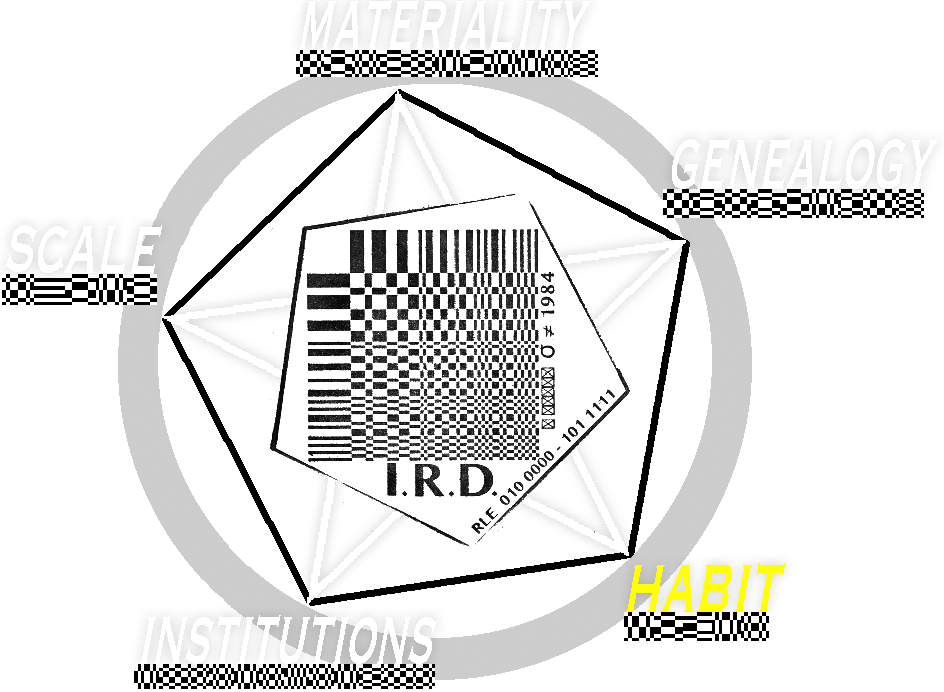

Resolution Dispute 0010 : Habit

[[part of Resolution Studies]]

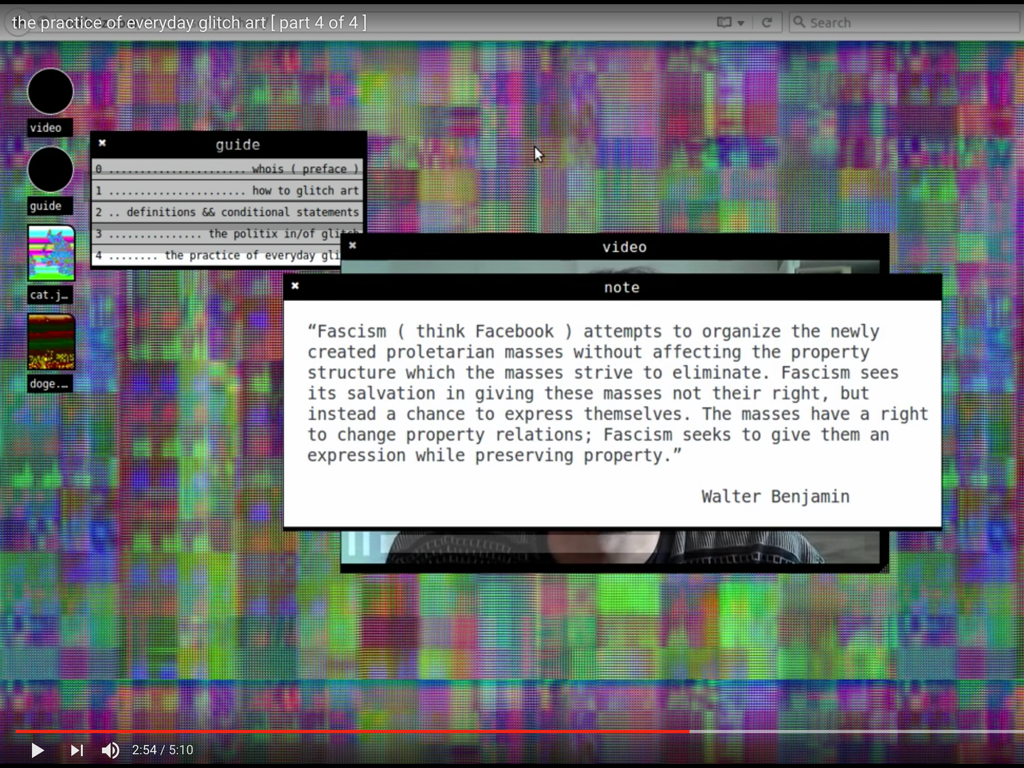

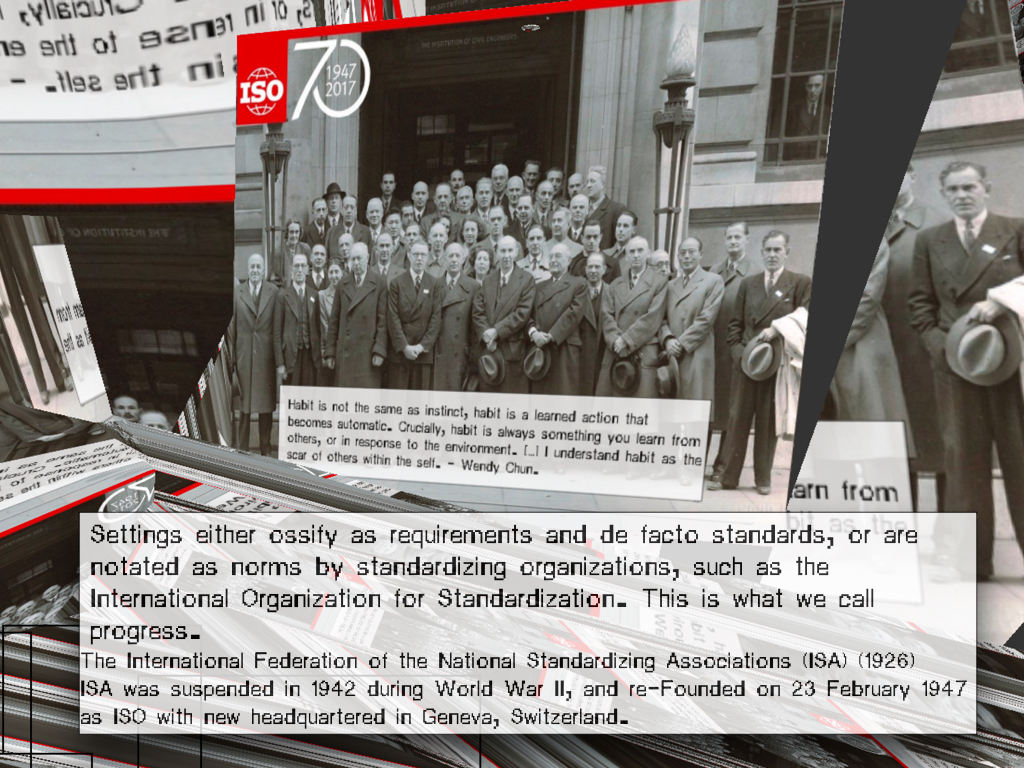

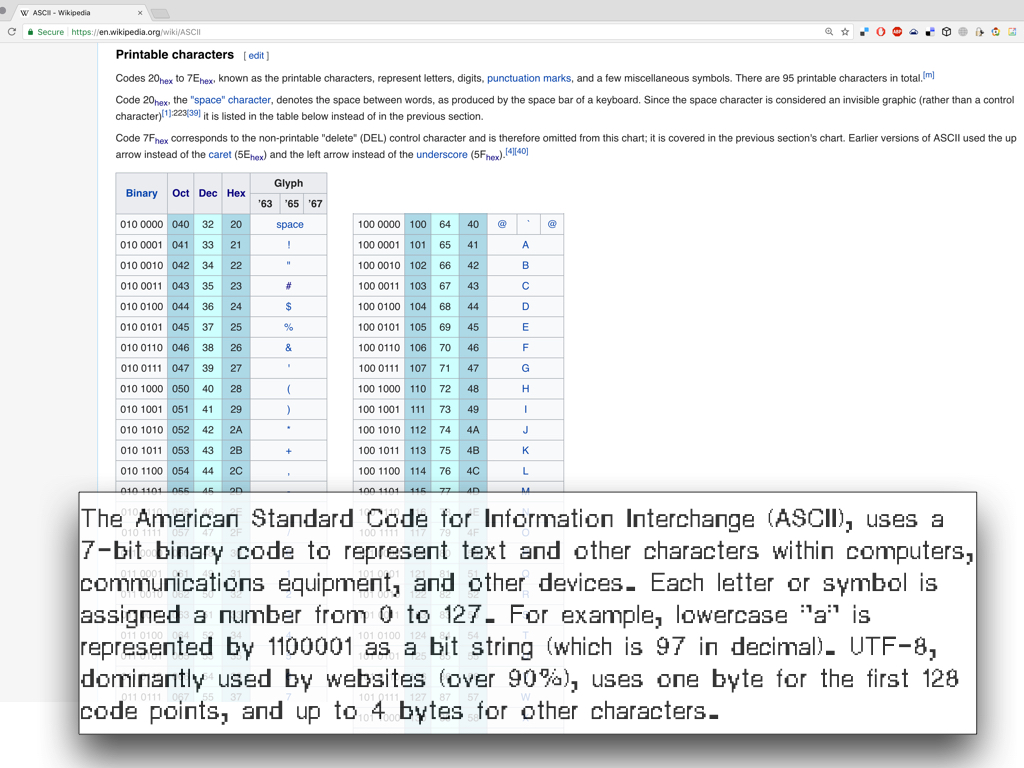

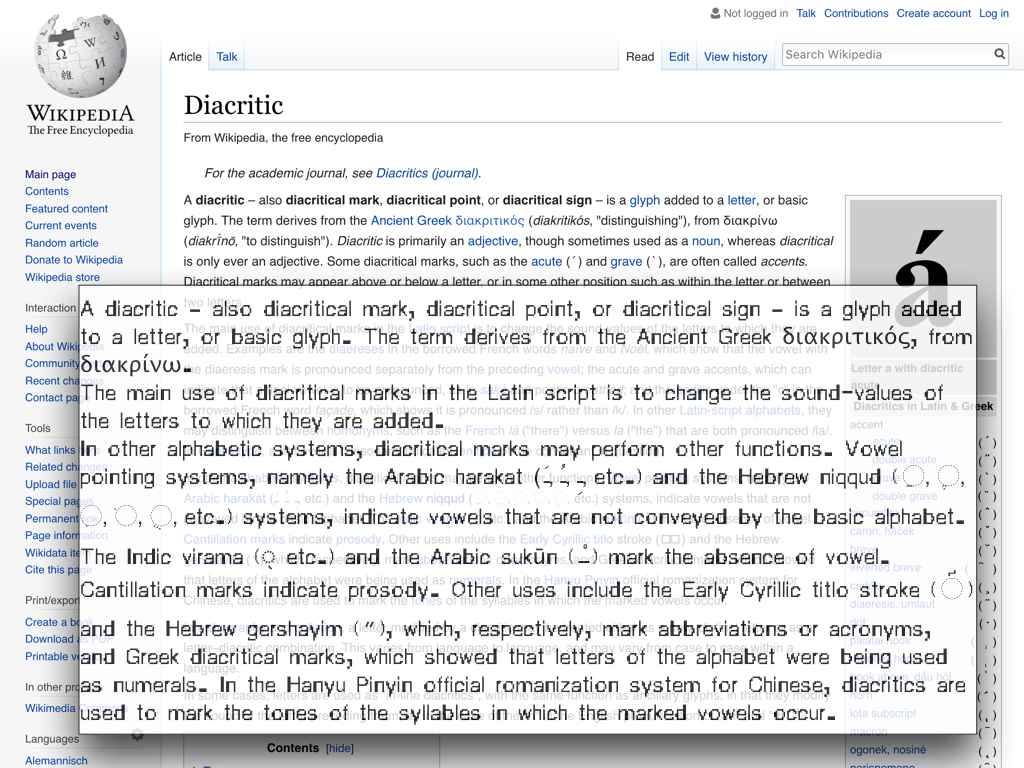

Following the ideal logic of transparent immediacy, technology is designed in such a way that the user will forget about the presence of the medium. Generally, technology aims to offer an uninterrupted flow of functionality and information. This concept of flow is not just a trait of the machine, but also a feature of society as a whole, writes DeLanda.1 DeLanda distinguishes between chaotic disconnected flows and stable flows of matter, that move in continuous variations, conveying singularities. DeLanda also references Deleuze and Guattari, who describe flow in terms of the beliefs and desires that both stimulate and maintain society.2 Deleuze and Guattari write that a flow is something that comes into existence over long periods of time. Within these periods, conventions, customs and individual habits are established, while deviations tend to become rare occurrences and are often (mis)understood as accidents (or in computation: glitches). Although the meaningfulness of every day life might in fact be disclosed within these rare occurances, their impact or relevance is often ruled out, because of social tendencies to emphasize the norm.

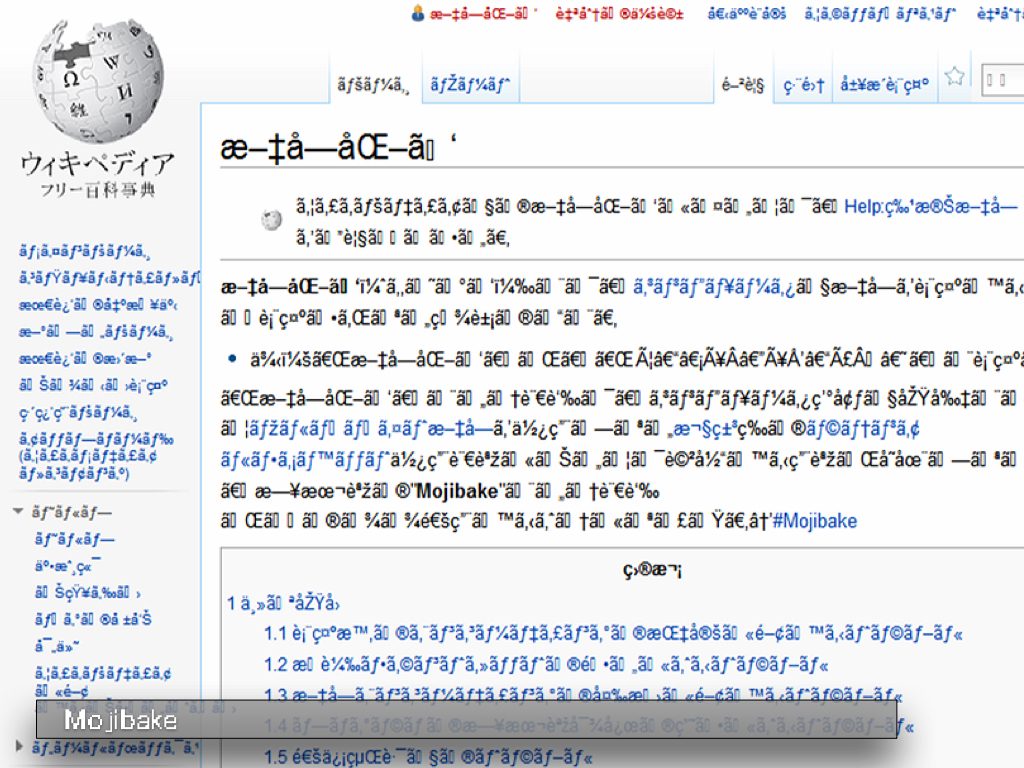

To move beyond resolution also means to move beyond the habitual. One way to do this is by creating noise, for instance in the form of glitch: a short lived fault or break from an expected flow of operation within a (digital) system. The glitch is a puzzling, difficult to define and enchanting noise artifact; it reveals itself as accident, chaos or laceration and gives a glimpse into normally obfuscated machine language. Rather than creating the illusion of a transparent, well-working interface to information, the glitch can impose both technological and perceptual challenges to habitual and ideological conventions. It shows the machine revealing itself. Suddenly, the computer appears unconventionally deep, in contrast to the more banal, predictable, surface-level behaviors of ‘normal’ machines and systems.

To really understand the complexity of the user’s perceptual experience it is important to focus on these rare occurances - to create an awareness of the users habits by use of, for instance, the accident.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

1. Manuel DeLanda, War in the Age of Intelligent Machines, New York: Zone Books, 1991. p. 20.

2. Gilles Deleuze and Pierre-Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Trans. B. Massumi, Londen: The Athlone Press, 1988. p. 219.

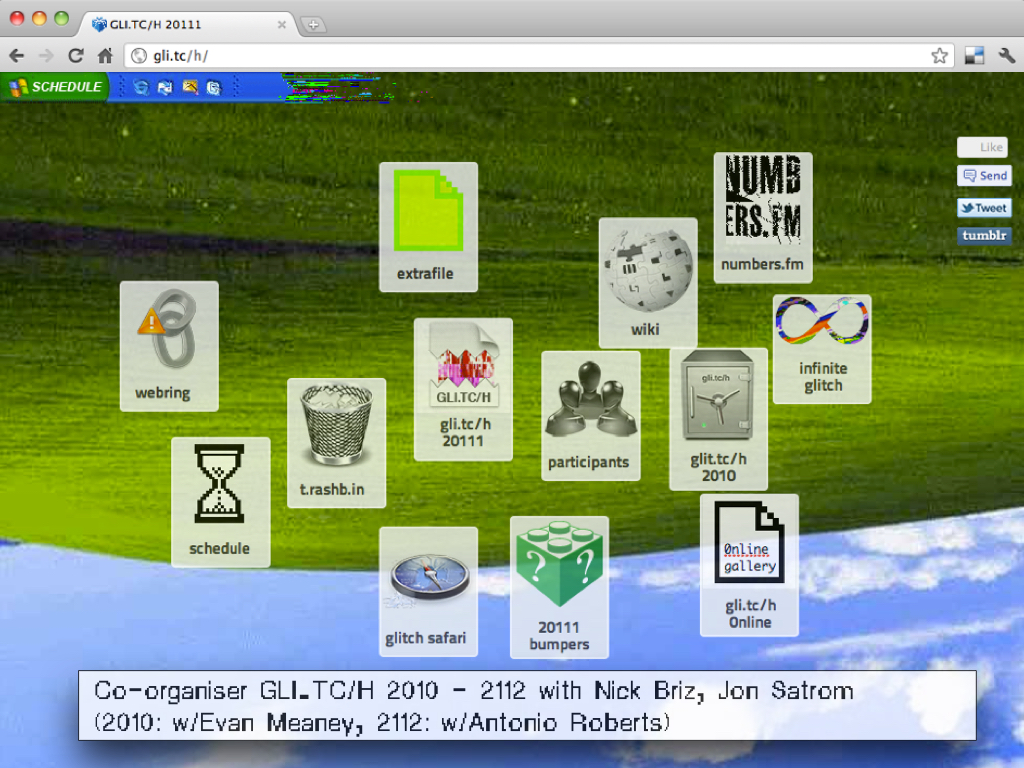

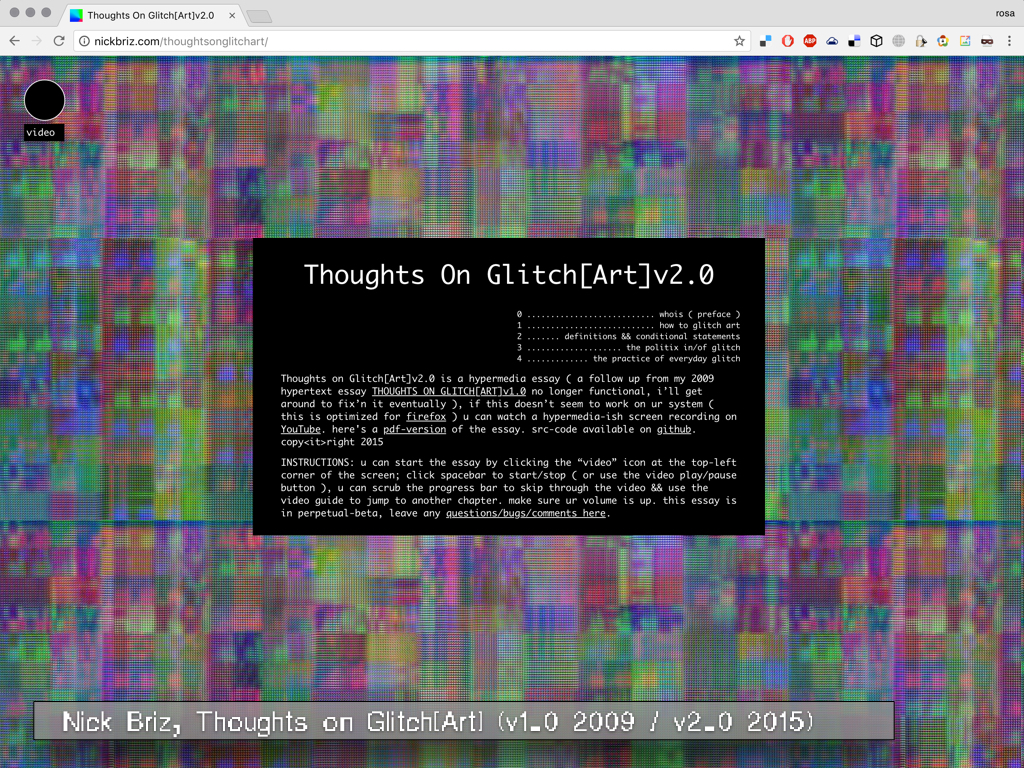

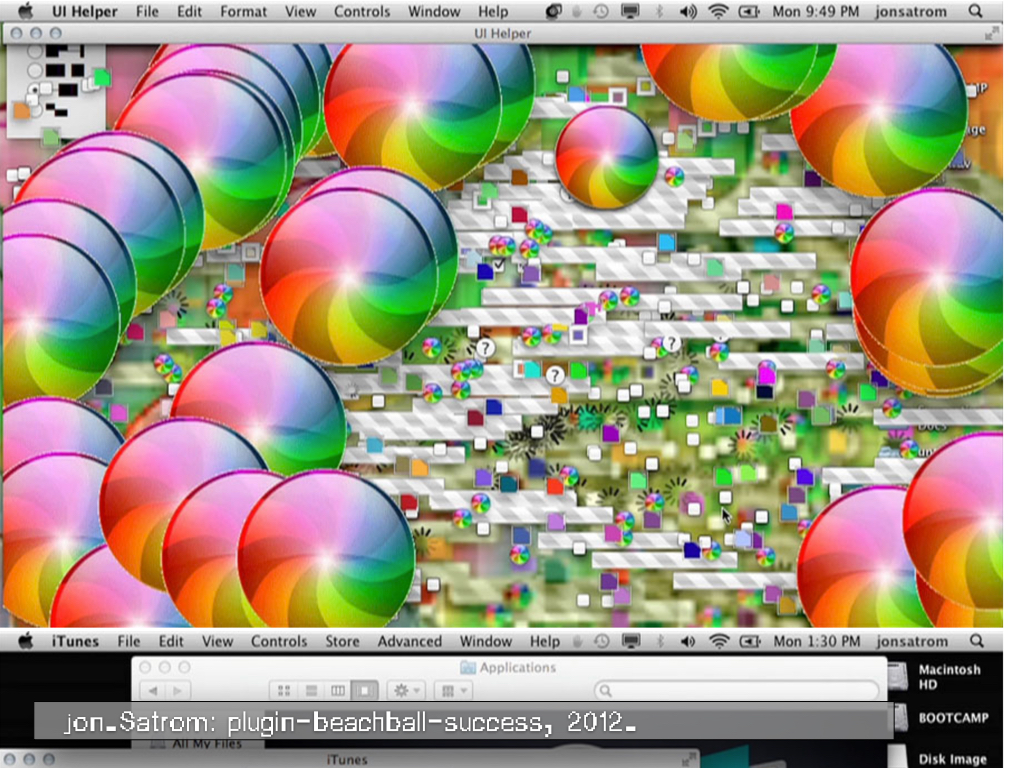

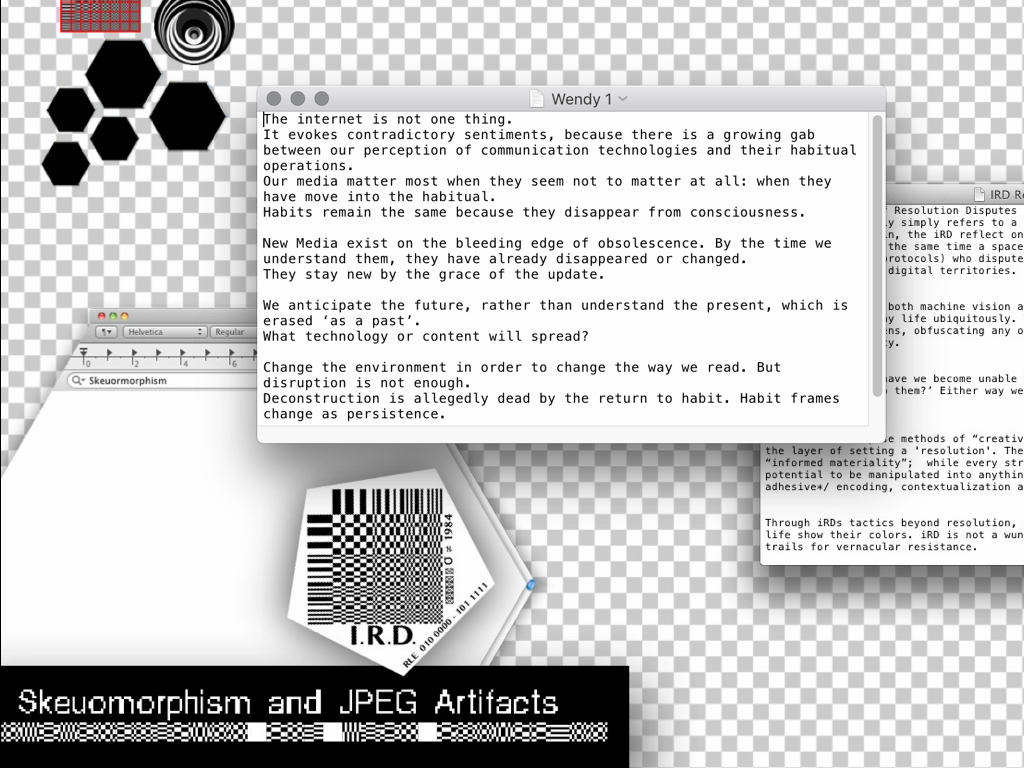

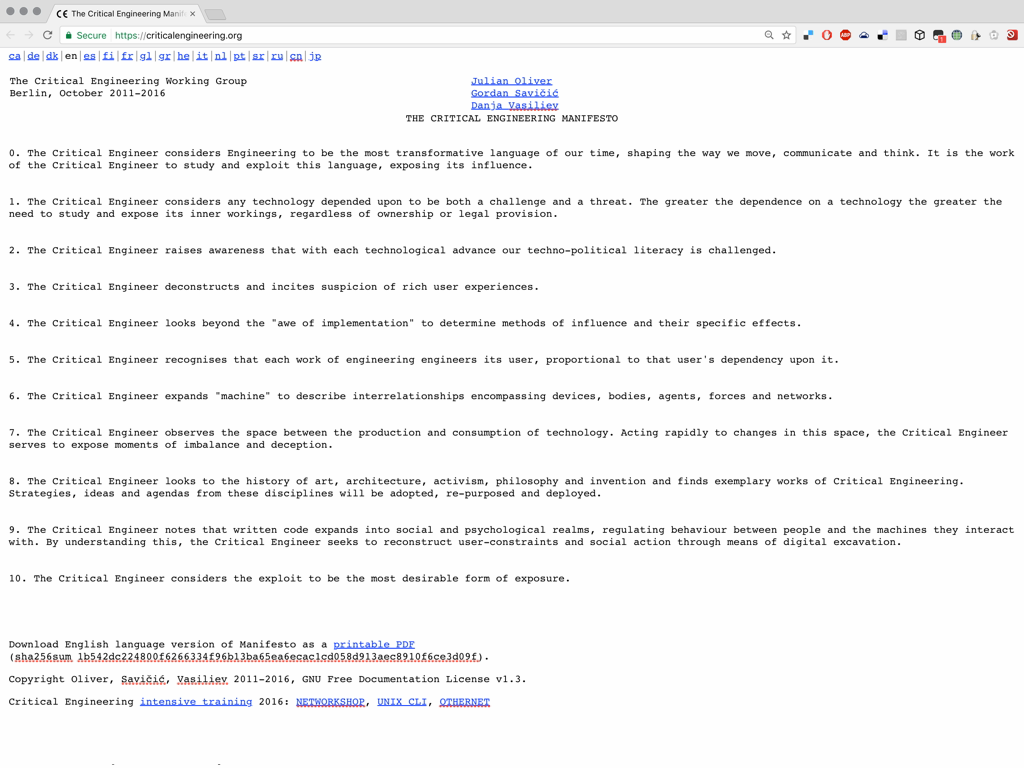

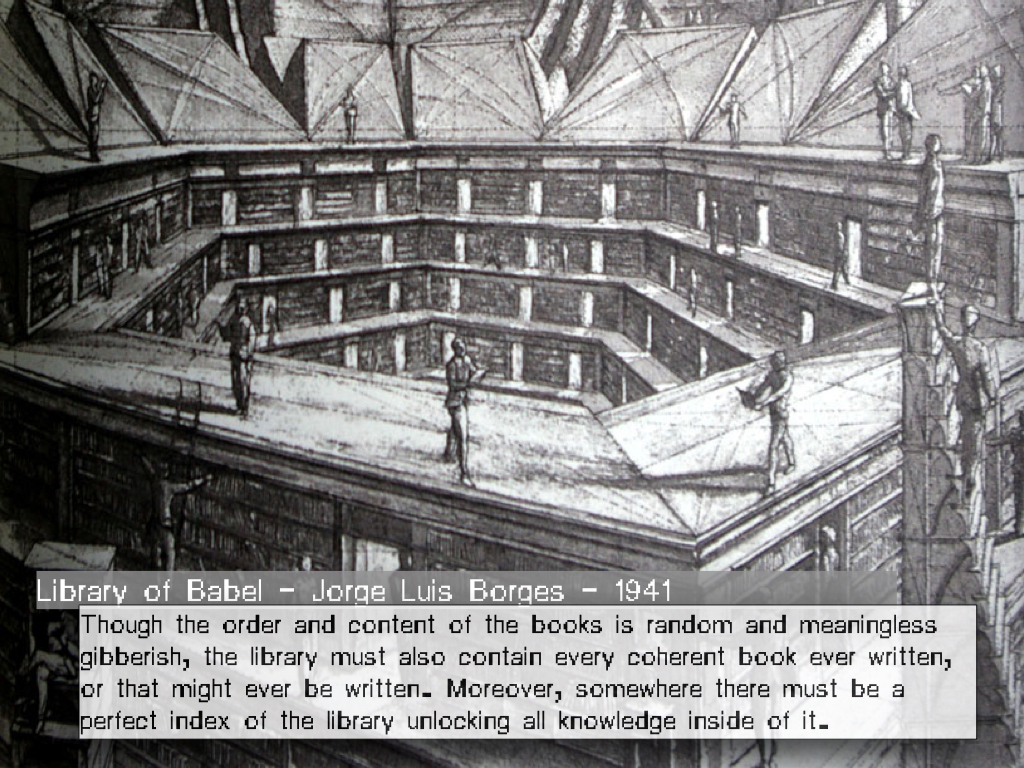

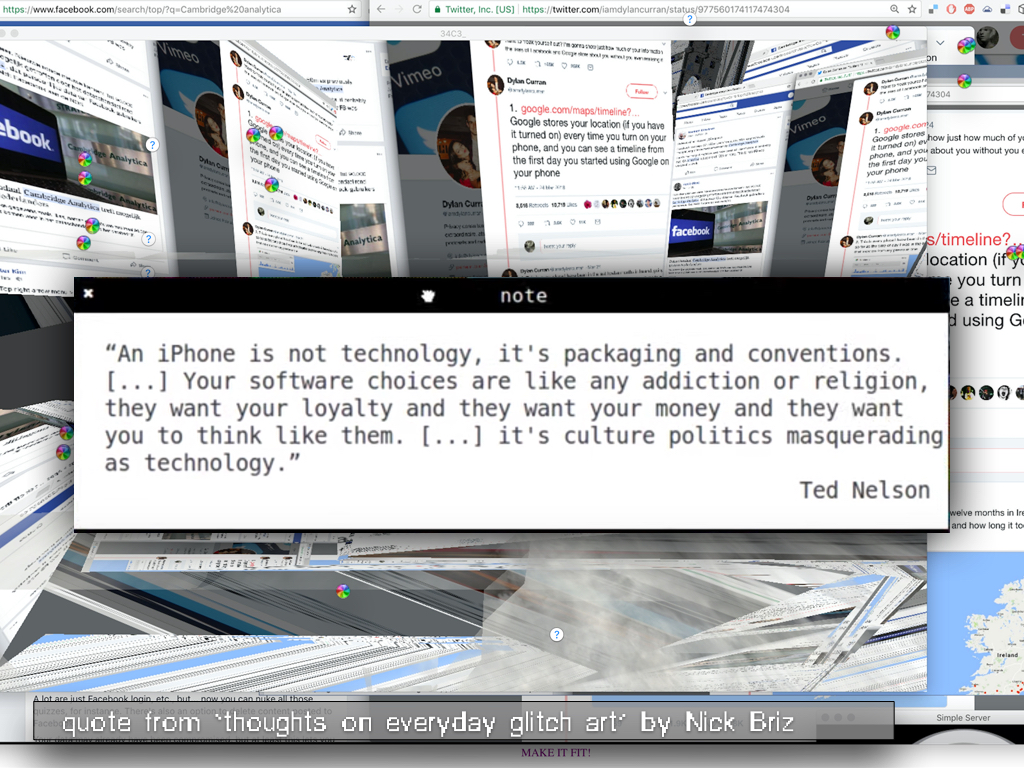

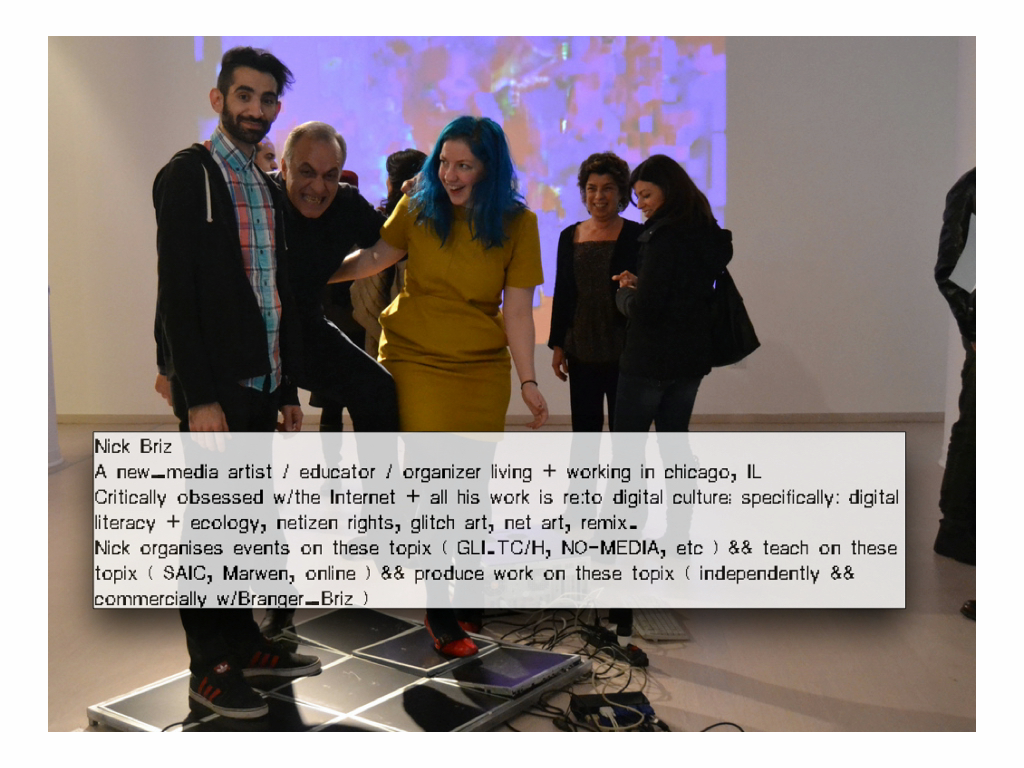

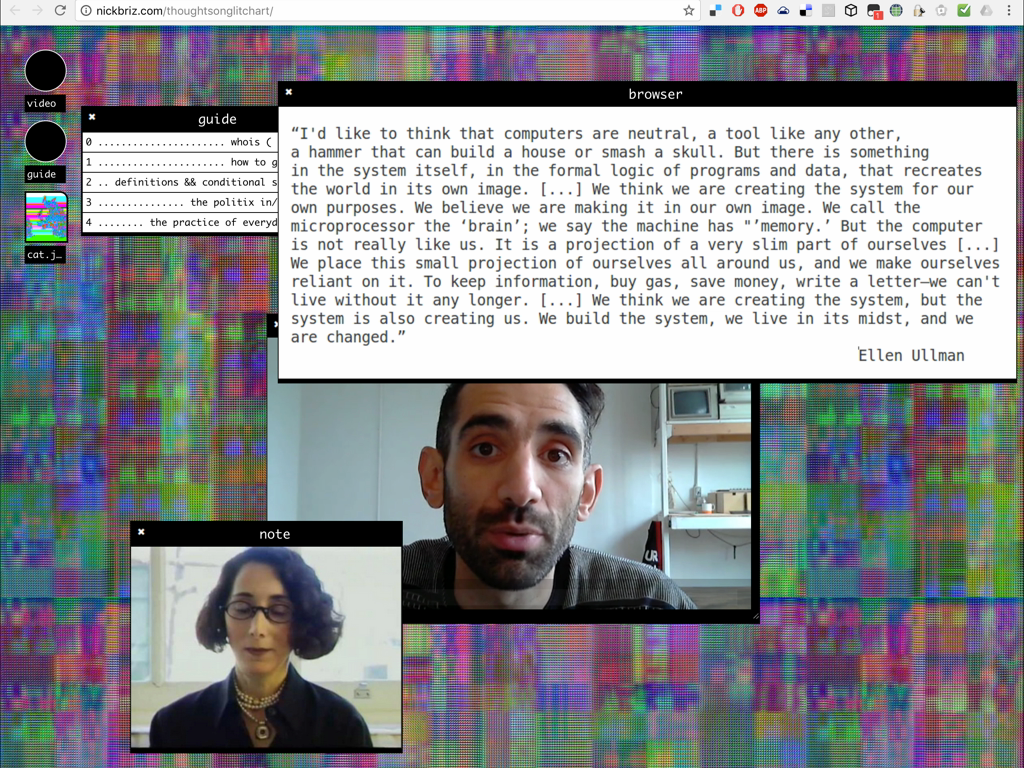

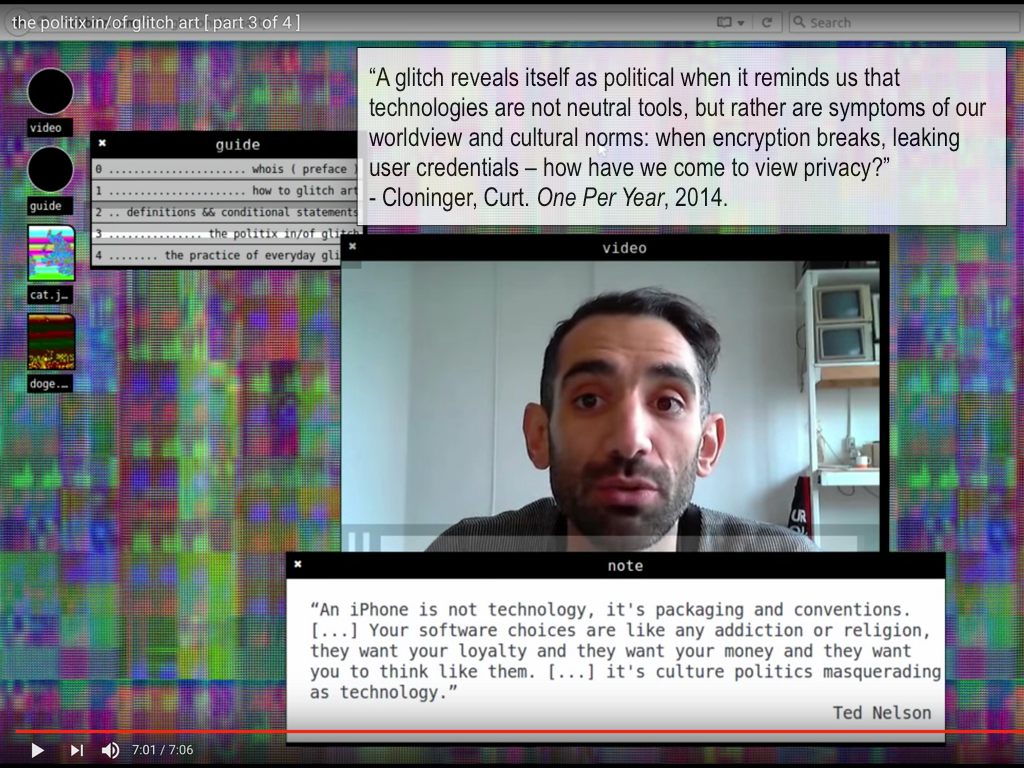

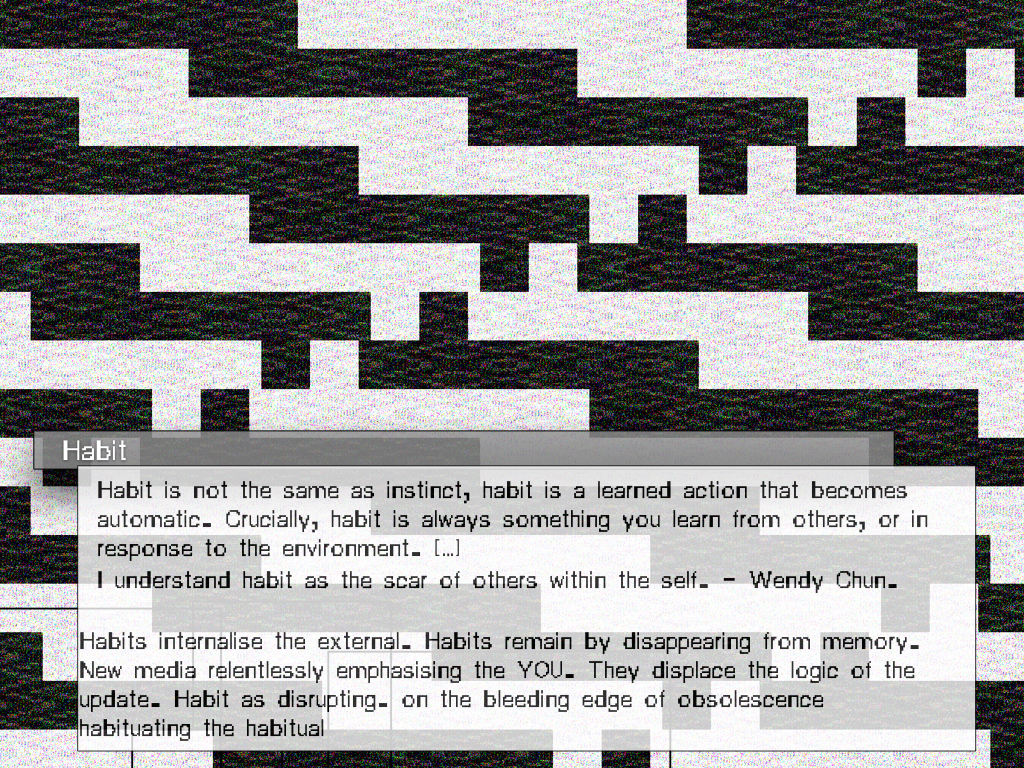

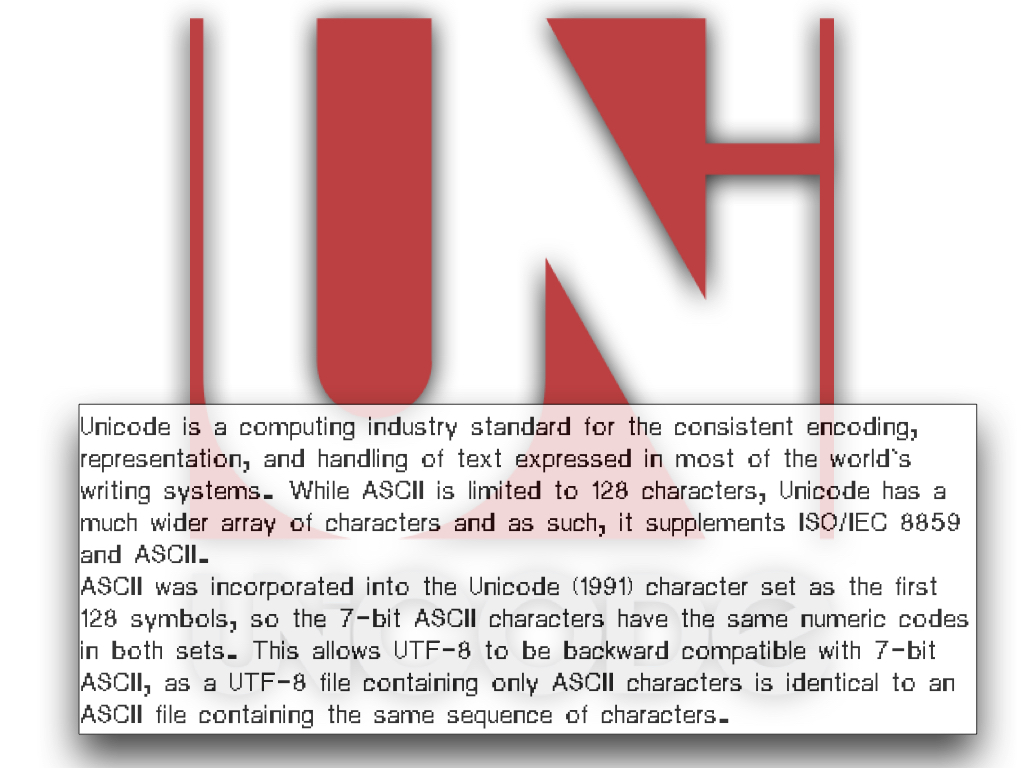

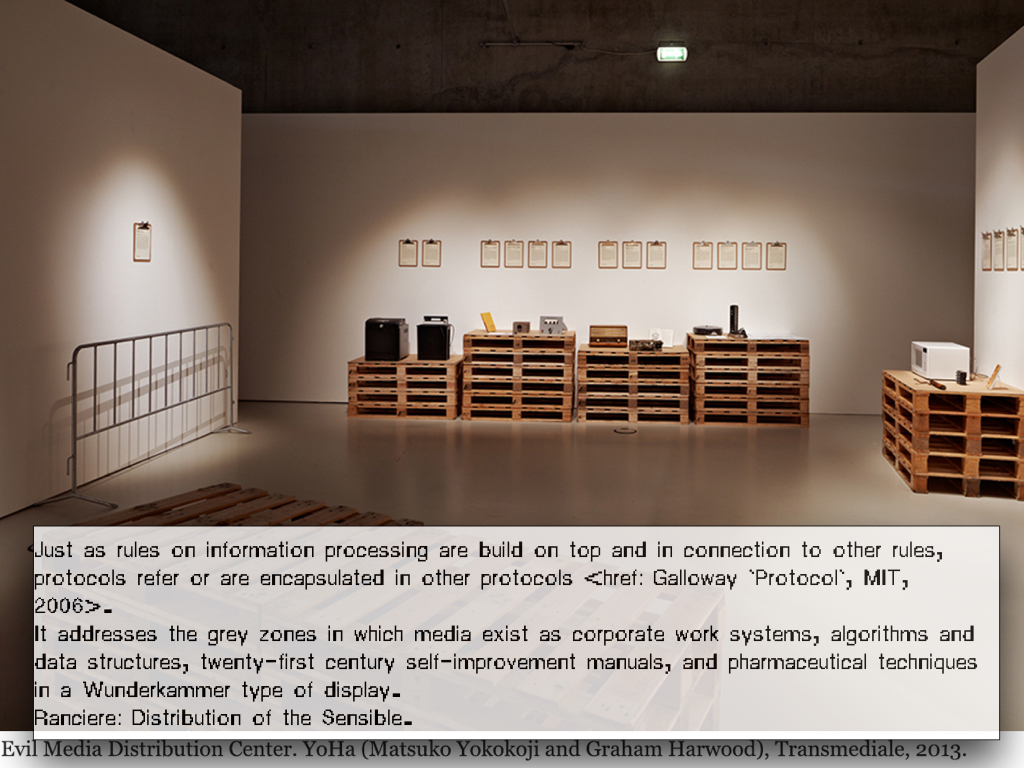

The slides underneath are from the New Media class ‘Beyond Resolution’ which I thaught as substitute professor at the KHK (Kassel) in the Sommer Semester of 2018. During this week we unpacked the term ‘Habitual Use’ via a research into various layers of standardization. The slides are clickable; they either link to the work reference or zoom.

[︎]

Jodi on the Rack

[Jodi op de pijnbank]

Master thesis in Dutch (2006), supervised by Joost Bolten.

Introduction

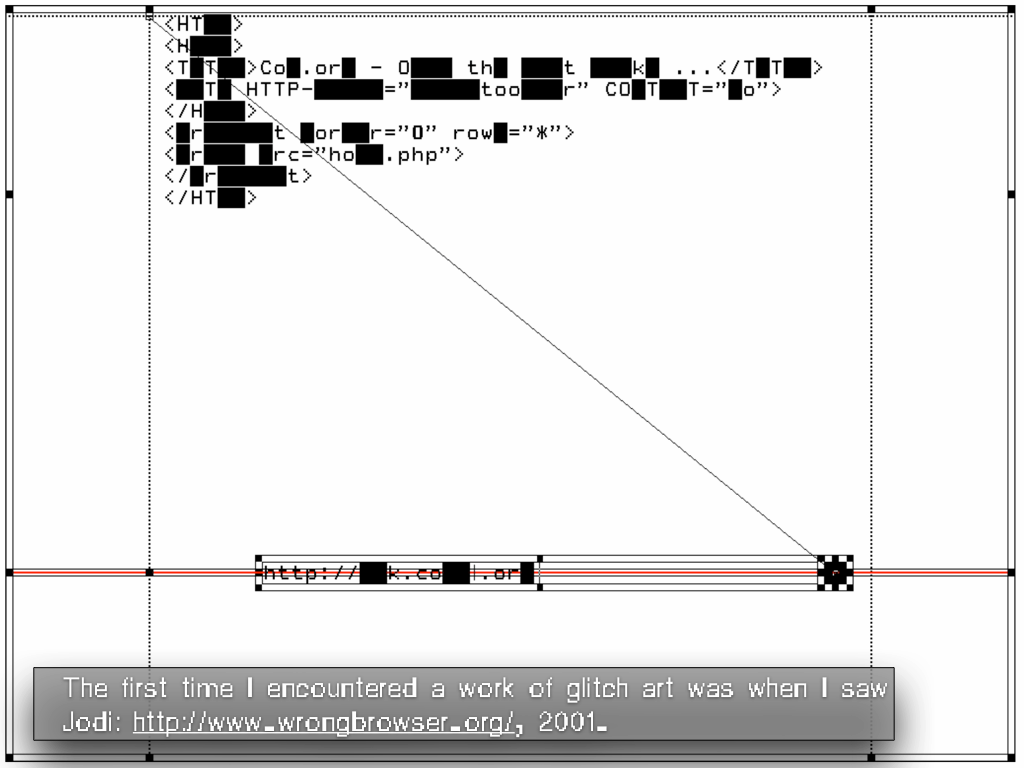

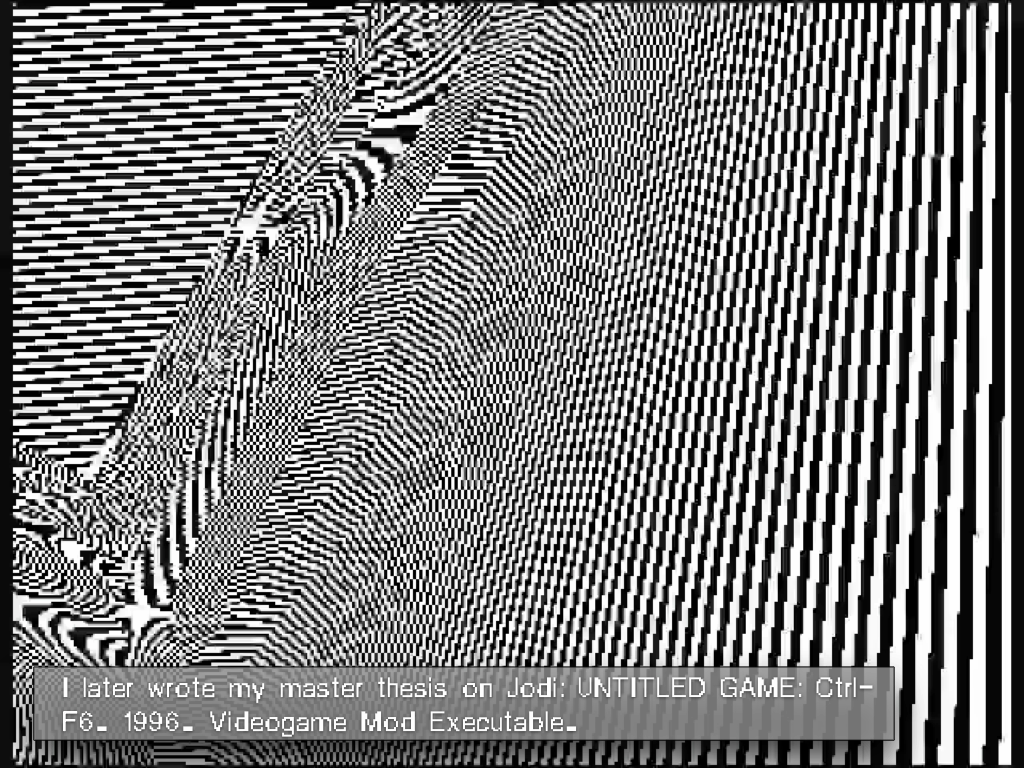

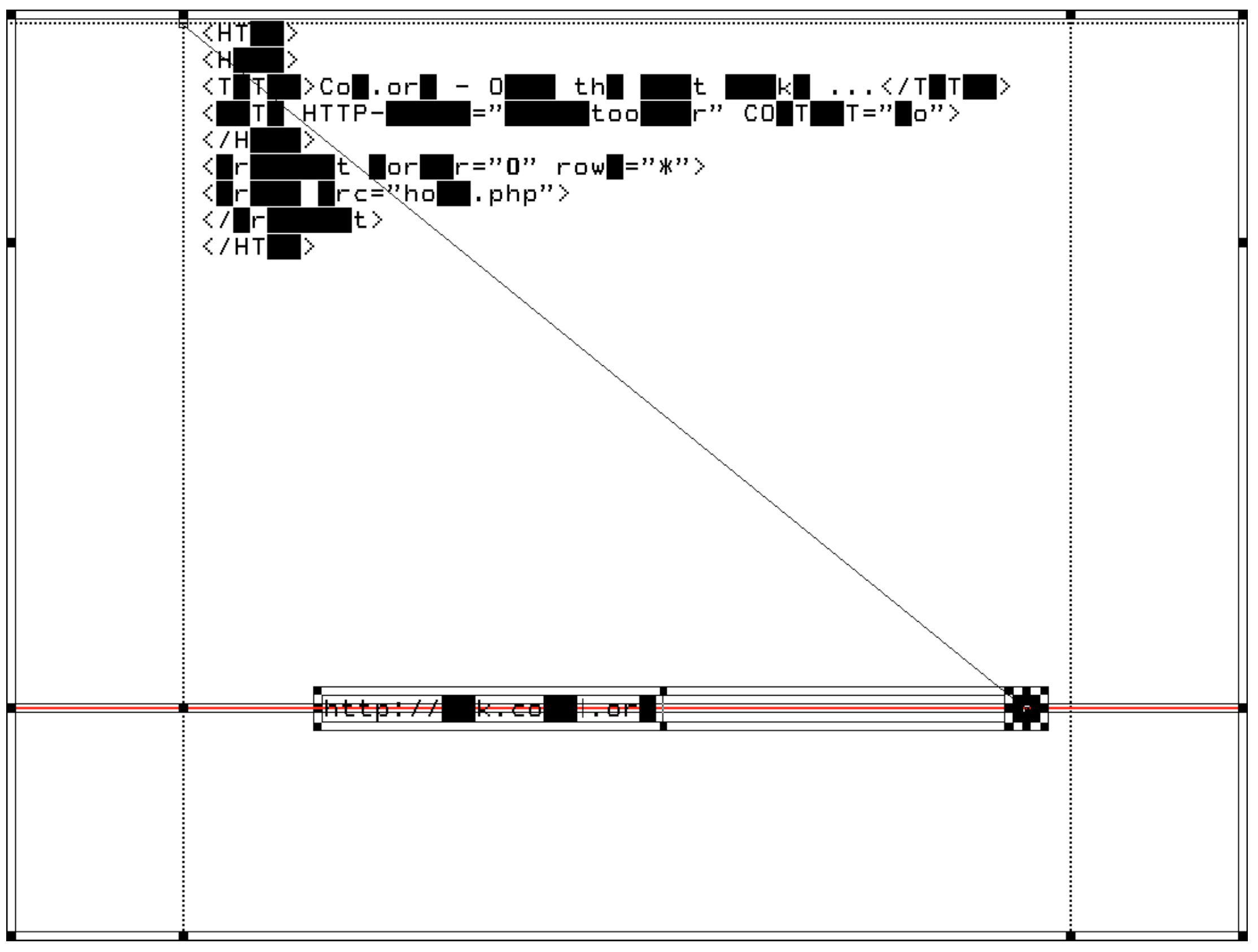

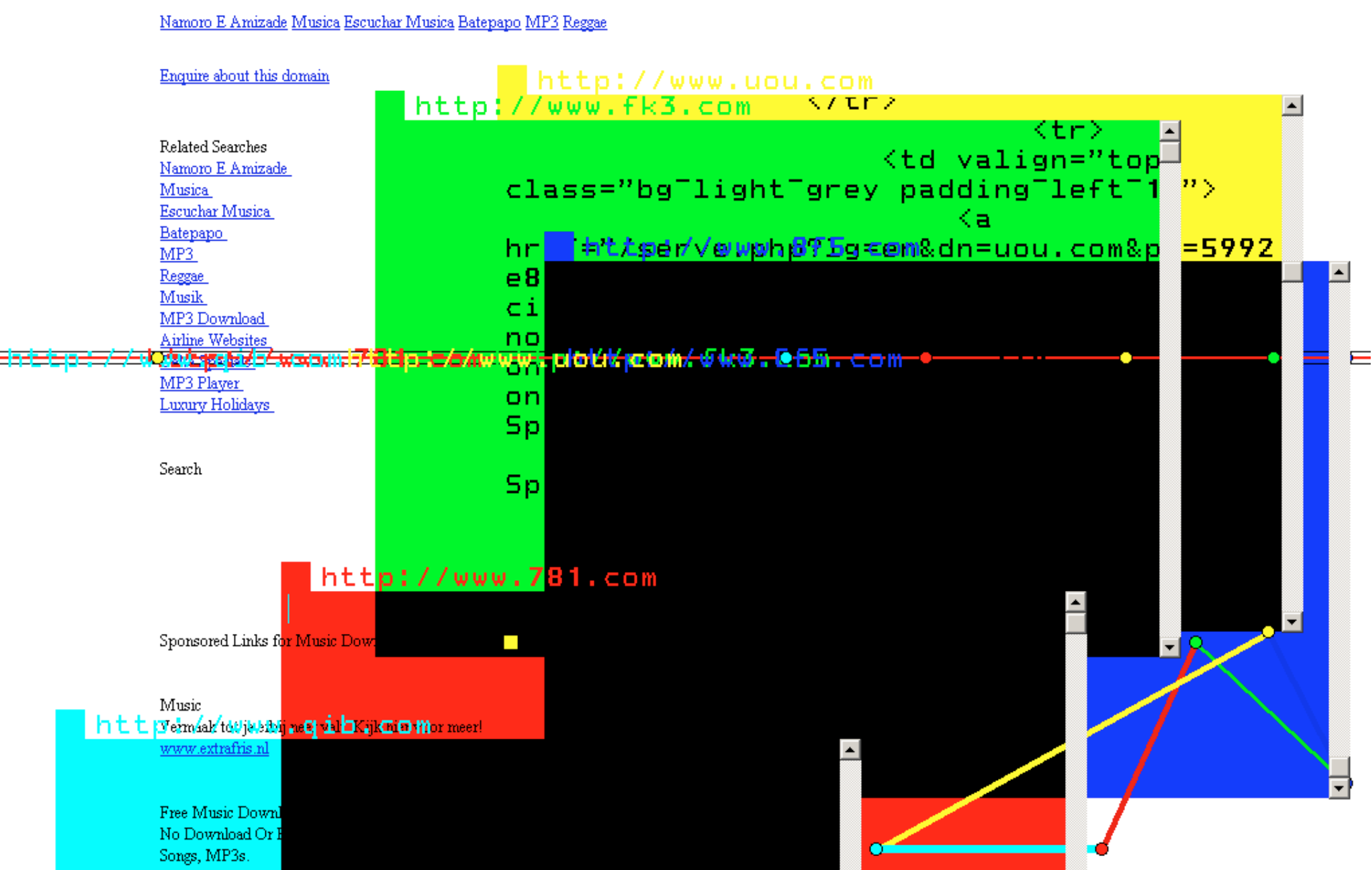

In October 2005 I visited the World Wide Wrong, a solo show from the Dutch/Belgium artist collective Jodi (Jo for Joan Heemskerk and di for Dirk Paesmans) in Montevideo, the Institute for Media Arts in Amsterdam.

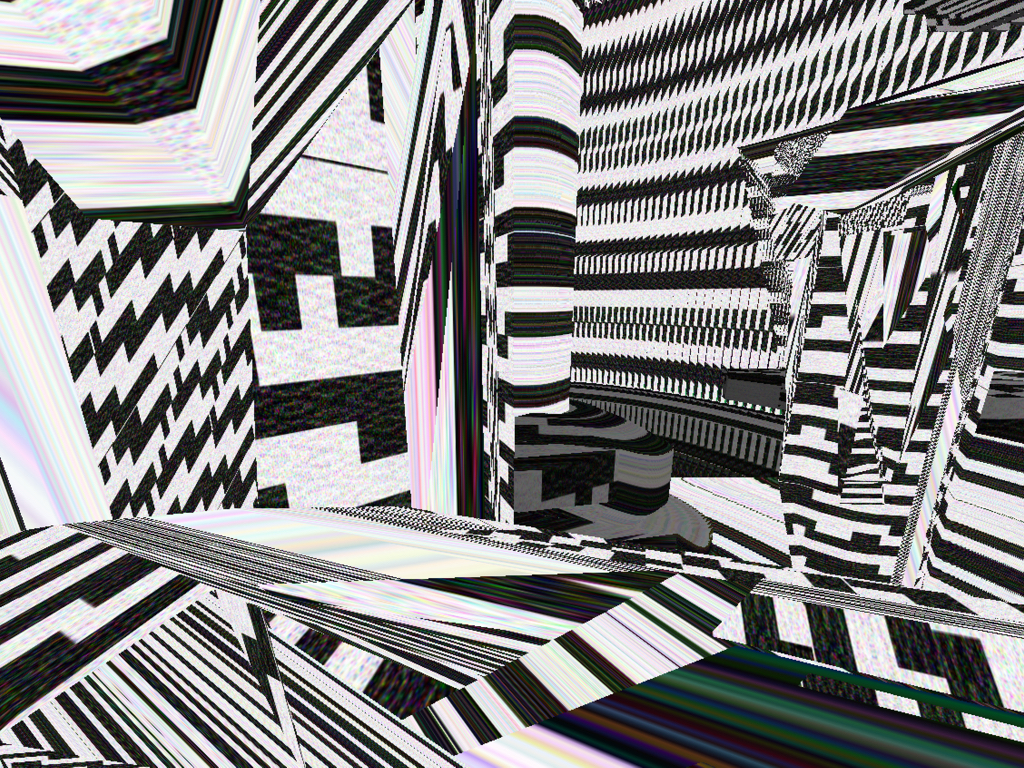

Untitled Game (Jodi, 1996) was one of the works on display. I immediately recognised the game Quake 1 (id software, 1996), of which Untitled Game is a collection of mods. At first, the confrontation with these mods was confusing, but after reading the texts that accompanied the exhibition, I understood the work better; my associations with the game Quake had mislead my first interpretations - I had let my previous experiences lead my reading of the work and Jodi had played with this habitual pattern of expectation.

This was my first experience with digital art that played with the norms and expectations of digital material. Untitled Game was an eye-opener. I realised there were new, changing and evolving differences not only between traditional ‘high art’ and contemporary, interactive ‘high art’, but also between art and entertainment. What intrigued me most, however, was that the work of Jodi, an art collective that does not follow any traditions, is still part of a canon of ‘high art’ and has won quite a few important prices!

The debate around art and the videogame industry has grown in intensity since the exhibition The Next Level in the Stedelijk Museum Centraal Station (SMCS). The exhibition got a lot of publicity and has been visited by both the game community as well as the normal museum crowd and received some critical feedback from both sides. Merel Roze wrote a critical piece titled ‘Games = Art’. From this piece it seemed like the question if a popular mass medium belongs to the space of the contemporary museum is again relevant.

These developments made me think more deeply about the medium of Untitled Game - the computergame; how does this technology actually work, and how does the medium in which the work is disseminated and institutionalised (the internet, the museum and the art discourse) influence the (understanding of the) work. These are the questions I wish to analyse in this thesis. I am using the word analyse here in quite a literal way - I will take Untitled Game apart for a more close-up understanding, using the metaphor of a medieval ‘rack’; a technique used in torture - to force a subject to answer during questioning.

During this questioning of Jodi and Untitled Game, I will limit myself to five perspectives; in chapter one I will describe the art collective Jodi and the work. The following chapter I will dedicate to the difference and tension between high art and popular culture, to position Untitled Game within the perspective of critical theory. In the third chapter I will describe Untitled Game from an aesthetical point of view. Here I am not just using the classic, rather passive meaning of aesthetics, referring to passive contemplation, but also using the term in a more active form. In doing so, I wish to come back to a more philosophical meaning of the term esthetics. In the fourth chapter, I will describe Untitled Game from a technological and art historical point of view. Finally, in chapter five - I will describe the work as an ephemeral work of art.

︎ Jodi op de pijnbank (Dutch)

︎ bijlagen Jodi op de pijnbank (Dutch)

[ manifesto ]

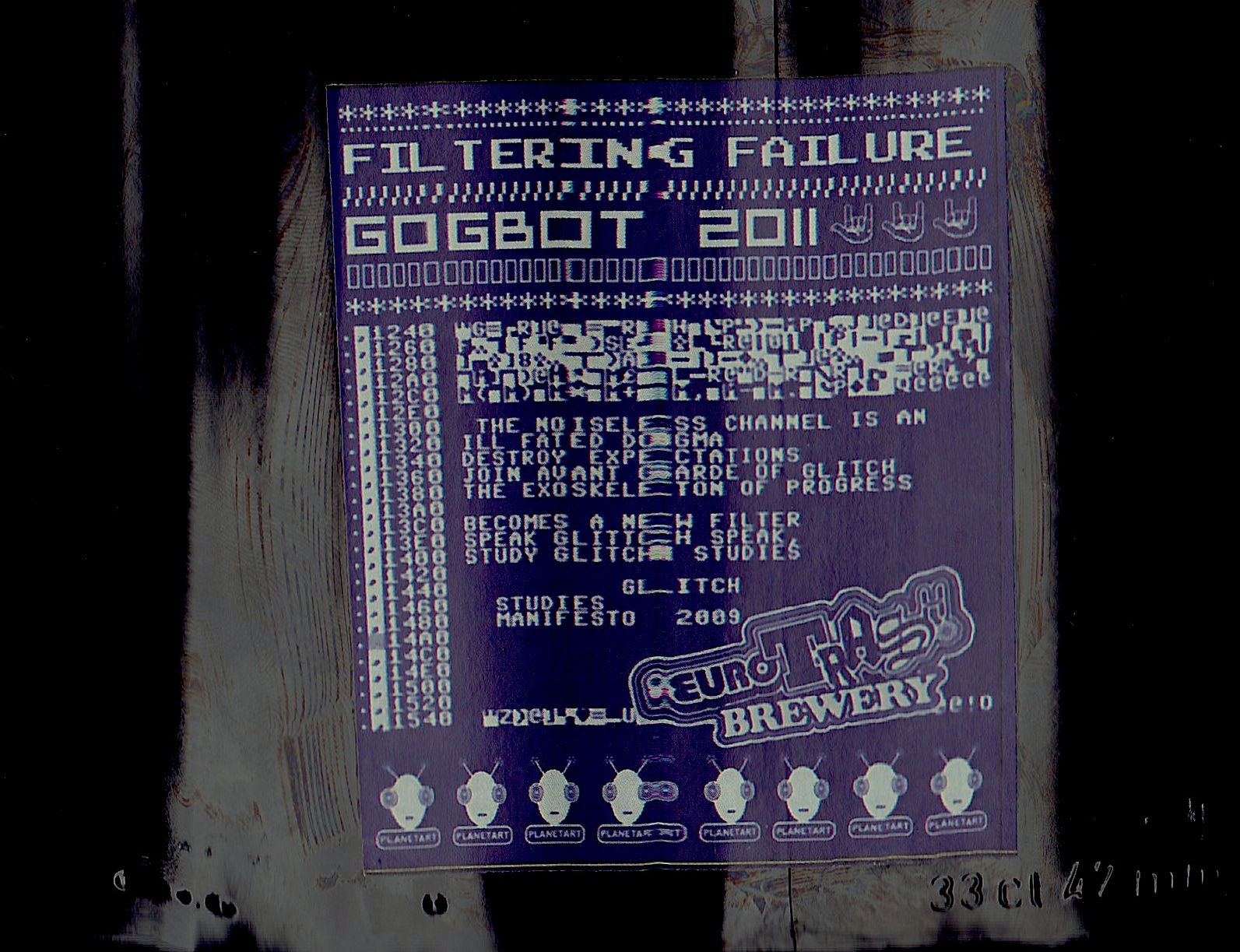

Filtering failure home brew by EuroTrash Brewery

Filtering failure home brew by EuroTrash Brewery

glitch:

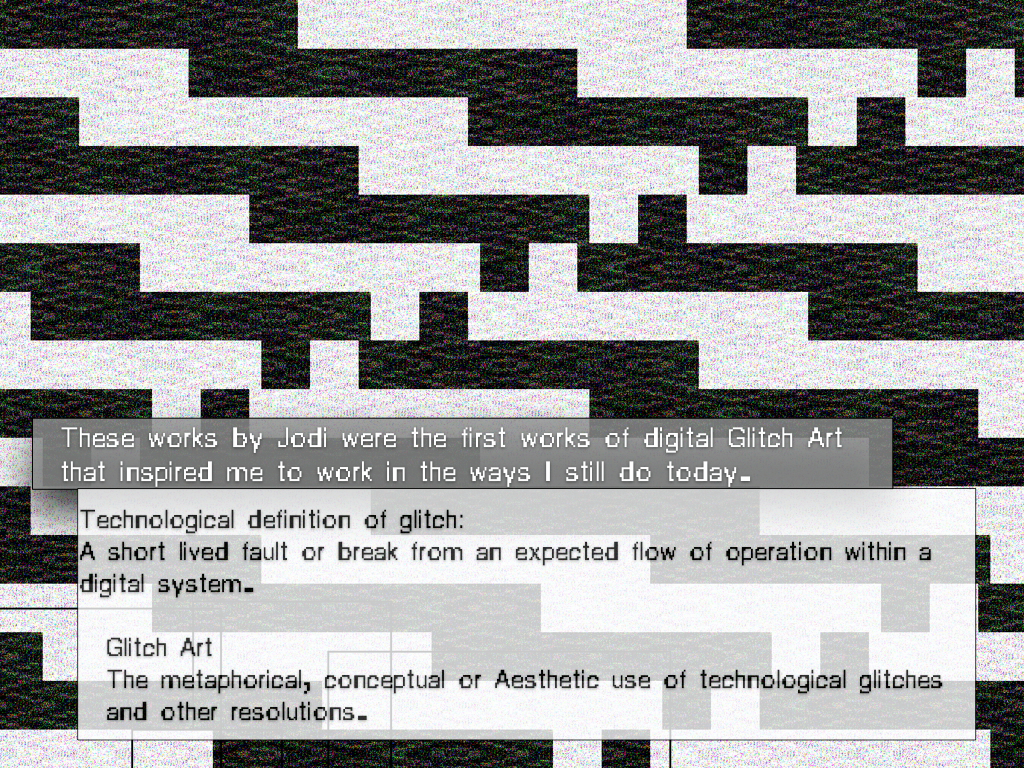

Technological definition of glitch:

A short lived fault or break from an expected flow of operation within a digital system.

Glitch Art: The metaphorical, conceptual or Aesthetic use of technological glitches and other resolutions within the realm of art.

Technological definition of glitch:

A short lived fault or break from an expected flow of operation within a digital system.

Glitch Art: The metaphorical, conceptual or Aesthetic use of technological glitches and other resolutions within the realm of art.

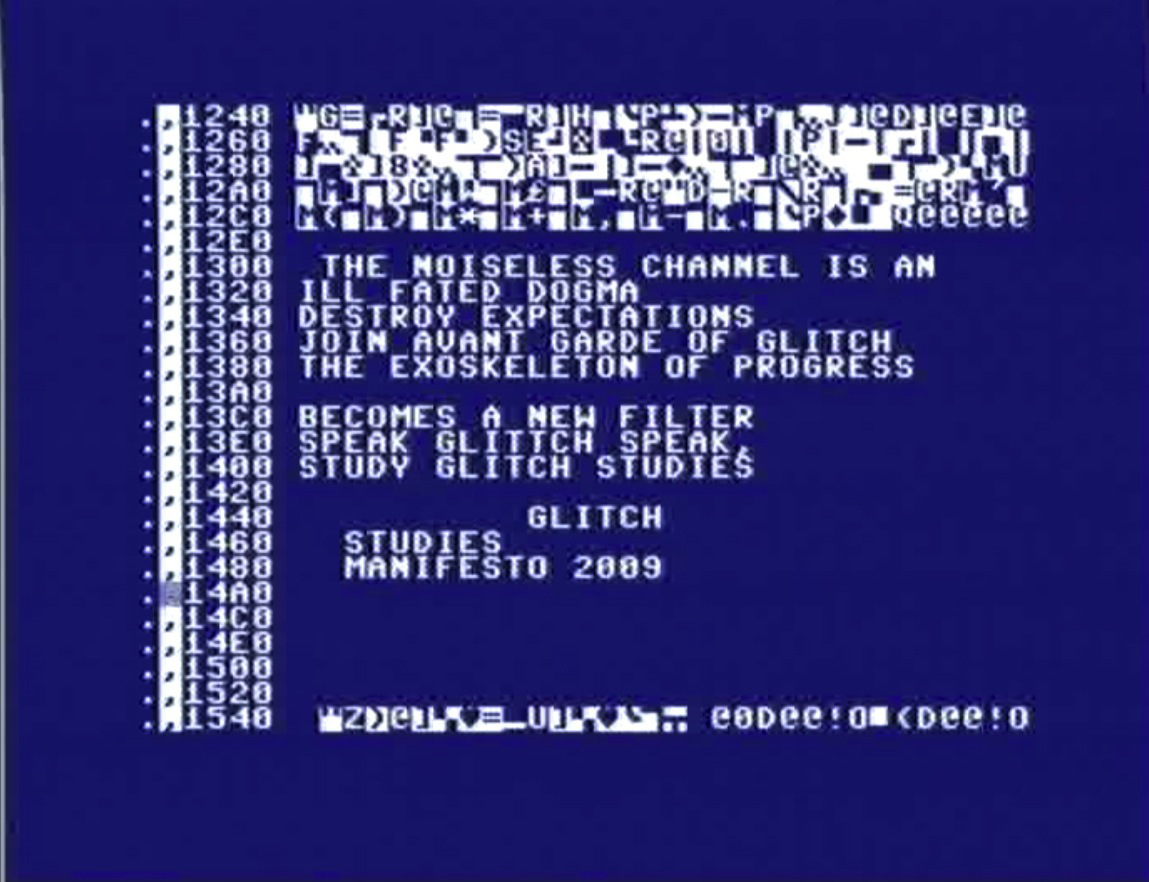

Glitch Studies Manifesto (short version)

1. The dominant, continuing search for a noiseless channel has been – and will always be – no more than a regrettable, ill-fated dogma.

Acknowledge that although the constant search for complete transparency brings newer, ‘better’ media, every one of these improved techniques will always possess their own inherent fingerprints of imperfection.

2. Dispute the operating templates of creative practice; fight genres, interfaces and expectations!

Refuse to stay locked into one medium or between contradictions like real vs. virtual, obsolete vs. up-to-date, open vs. proprietary or digital vs. analog. Surf the vortex of technology, the in-between, the art of artifacts!

.

3. Get away from the established action scripts and join the avant-garde of the unknown. Become a nomad of noise artifacts!

The static, linear notion of information-transmission can be interrupted on three occasions: during encoding-decoding (compression), feedback or when a glitch (an unexpected break within the flow of technology) occurs. Noise artists must exploit these noise artifacts and explore the new opportunities they provide.

4. Employ bends and breaks as metaphors for différance. Use the glitch as an exoskeleton for progress.

Find catharsis in disintegration, ruptures and cracks; manipulate, bend and break any medium towards the point where it becomes something new; create glitch art.

5. Realize that the gospel of glitch art also reveals new standards implemented by corruption. Not all glitch art is progressive or something new.

The popularization and cultivation of the avant-garde of mishaps has become predestined and unavoidable. Be aware of easily reproducible glitch effects automated by softwares and plug-ins. What is now a glitch will become a fashion.

6. Force the audience to voyage through the Acousmatic Videoscape.

Create conceptually synaesthetic artworks, that exploit both visual and aural glitch (or other noise) artifacts at the same time. Employ these noise artifacts as a nebula that shroudsthe technology and its inner workings and that will compel an audience to listen and watch more exhaustively.

7. Rejoice in the critical trans-media aesthetics of glitch artifacts.

Utilize glitches to bring any medium in a critical state of hypertrophy, to (subsequently) criticize its inherent politics.

8. Employ Glitchspeak (as opposed to Newspeak) and study what is outside of knowledge. Glitch theory is what you can just get away with!

Flow cannot be understood without interruption, nor can function without (the possibility of) glitching. This is why glitch studies is necessary.

Longer versions:

︎old || ︎ new

︎ Polish translation by Bogumiła Piotrowska, Piotr Puldzian Płucienniczak, Aleksandra Pieńkosz

︎ Portuguese translation by Italo Dantas

︎ Turkish translation by Burak Ş. Çelik

︎ Persian translation by Nazila Karimi

︎ Spanish translation for Holobionte

︎ German translation (to come)

1. The dominant, continuing search for a noiseless channel has been – and will always be – no more than a regrettable, ill-fated dogma.

Acknowledge that although the constant search for complete transparency brings newer, ‘better’ media, every one of these improved techniques will always possess their own inherent fingerprints of imperfection.

2. Dispute the operating templates of creative practice; fight genres, interfaces and expectations!

Refuse to stay locked into one medium or between contradictions like real vs. virtual, obsolete vs. up-to-date, open vs. proprietary or digital vs. analog. Surf the vortex of technology, the in-between, the art of artifacts!

.

3. Get away from the established action scripts and join the avant-garde of the unknown. Become a nomad of noise artifacts!

The static, linear notion of information-transmission can be interrupted on three occasions: during encoding-decoding (compression), feedback or when a glitch (an unexpected break within the flow of technology) occurs. Noise artists must exploit these noise artifacts and explore the new opportunities they provide.

4. Employ bends and breaks as metaphors for différance. Use the glitch as an exoskeleton for progress.

Find catharsis in disintegration, ruptures and cracks; manipulate, bend and break any medium towards the point where it becomes something new; create glitch art.

5. Realize that the gospel of glitch art also reveals new standards implemented by corruption. Not all glitch art is progressive or something new.

The popularization and cultivation of the avant-garde of mishaps has become predestined and unavoidable. Be aware of easily reproducible glitch effects automated by softwares and plug-ins. What is now a glitch will become a fashion.

6. Force the audience to voyage through the Acousmatic Videoscape.

Create conceptually synaesthetic artworks, that exploit both visual and aural glitch (or other noise) artifacts at the same time. Employ these noise artifacts as a nebula that shroudsthe technology and its inner workings and that will compel an audience to listen and watch more exhaustively.

7. Rejoice in the critical trans-media aesthetics of glitch artifacts.

Utilize glitches to bring any medium in a critical state of hypertrophy, to (subsequently) criticize its inherent politics.

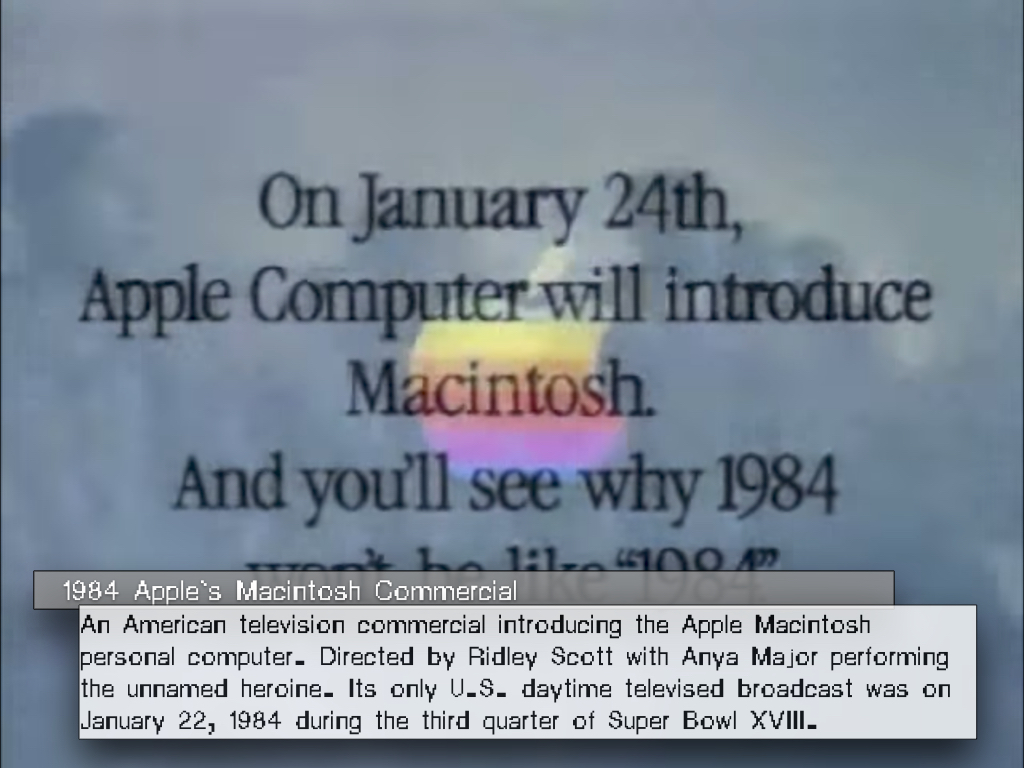

8. Employ Glitchspeak (as opposed to Newspeak) and study what is outside of knowledge. Glitch theory is what you can just get away with!

Flow cannot be understood without interruption, nor can function without (the possibility of) glitching. This is why glitch studies is necessary.

Longer versions:

︎old || ︎ new

︎ Polish translation by Bogumiła Piotrowska, Piotr Puldzian Płucienniczak, Aleksandra Pieńkosz

︎ Portuguese translation by Italo Dantas

︎ Turkish translation by Burak Ş. Çelik

︎ Persian translation by Nazila Karimi

︎ Spanish translation for Holobionte

︎ German translation (to come)

[ book ]

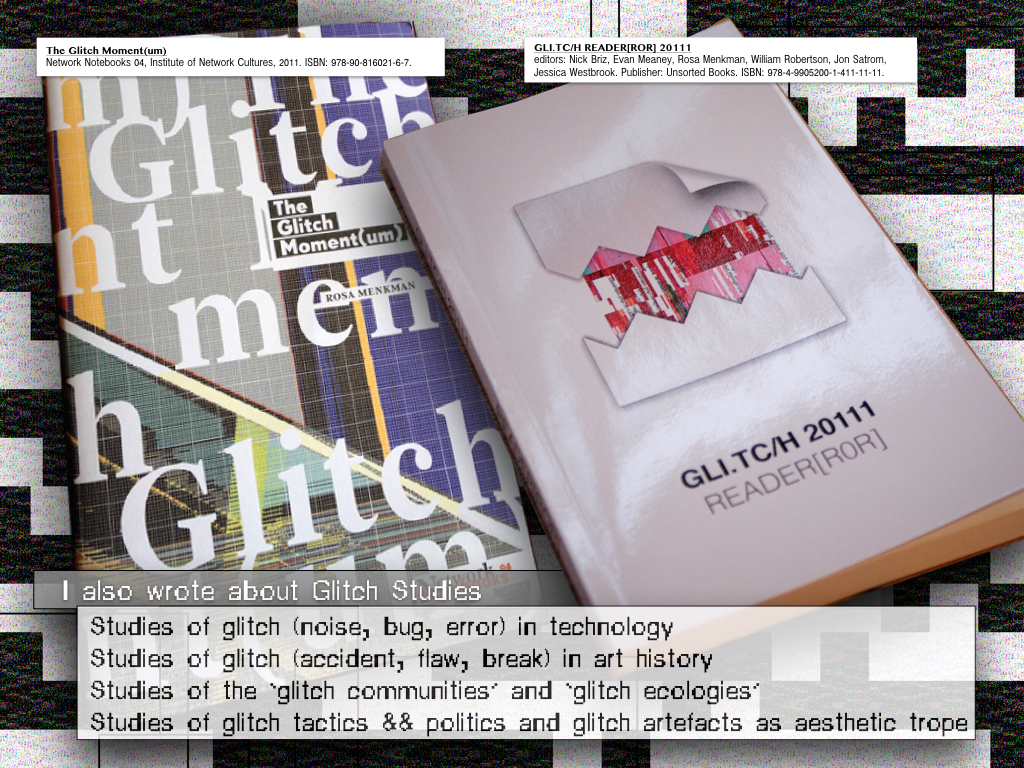

Glitch Moment/um (2011)

Published by the Institute of Network Cultures, December, 2011.

The Glitch Moment/um is the title of a small booklet I published in 2011. In the publication, I describe the moment of encountering a glitch as twofold:

First there is the moment the glitch happens, which is often experienced as an uncanny break of an expected technological flow or threatening loss of control. In this moment, the user or spectator doesn’t know what to expect next. This loss of control soon becomes a catalyst with a certain power as the glitch passes a tipping point. After its tipping point, the glitch is either understood as a failure, or as a development that forces new knowledge onto the user about their presumptions of the technology, or the technologies actual functioning. In case of the latter, the glitch can force the user to reconsider their habitual use of the technology.

After this experience of rupture, the glitch thus moves beyond its sublime momentum and vanishes into a realm of new conditions; it becomes a new mode - either technologically or aesthetically -, while its previous uncanny encounter is now an ephemeral, personal experience of a machine.

︎ From the INC Website

The Glitch Moment/um is the title of a small booklet I published in 2011. In the publication, I describe the moment of encountering a glitch as twofold:

First there is the moment the glitch happens, which is often experienced as an uncanny break of an expected technological flow or threatening loss of control. In this moment, the user or spectator doesn’t know what to expect next. This loss of control soon becomes a catalyst with a certain power as the glitch passes a tipping point. After its tipping point, the glitch is either understood as a failure, or as a development that forces new knowledge onto the user about their presumptions of the technology, or the technologies actual functioning. In case of the latter, the glitch can force the user to reconsider their habitual use of the technology.

After this experience of rupture, the glitch thus moves beyond its sublime momentum and vanishes into a realm of new conditions; it becomes a new mode - either technologically or aesthetically -, while its previous uncanny encounter is now an ephemeral, personal experience of a machine.

︎ From the INC Website

“Glitch culture organizes itself around the investigation and aestheticization of breaks in the conventional flow of information, or meaning within (digital) communication systems.

In this book, Rosa Menkman brings in early information theorists not usually encountered in glitch’s theoretical foundations to refine a signal and informational vocabulary appropriate to glitch’s technological moment/ums and orientations.”

A stranger like Dada / Weird like quaint collage ¯_( ͡ఠʘᴥ ⊙ಥ‶ʔ)ノ/̵͇̿̿/̿ ̿ ̿☞

“Your work is so.. so weird…”

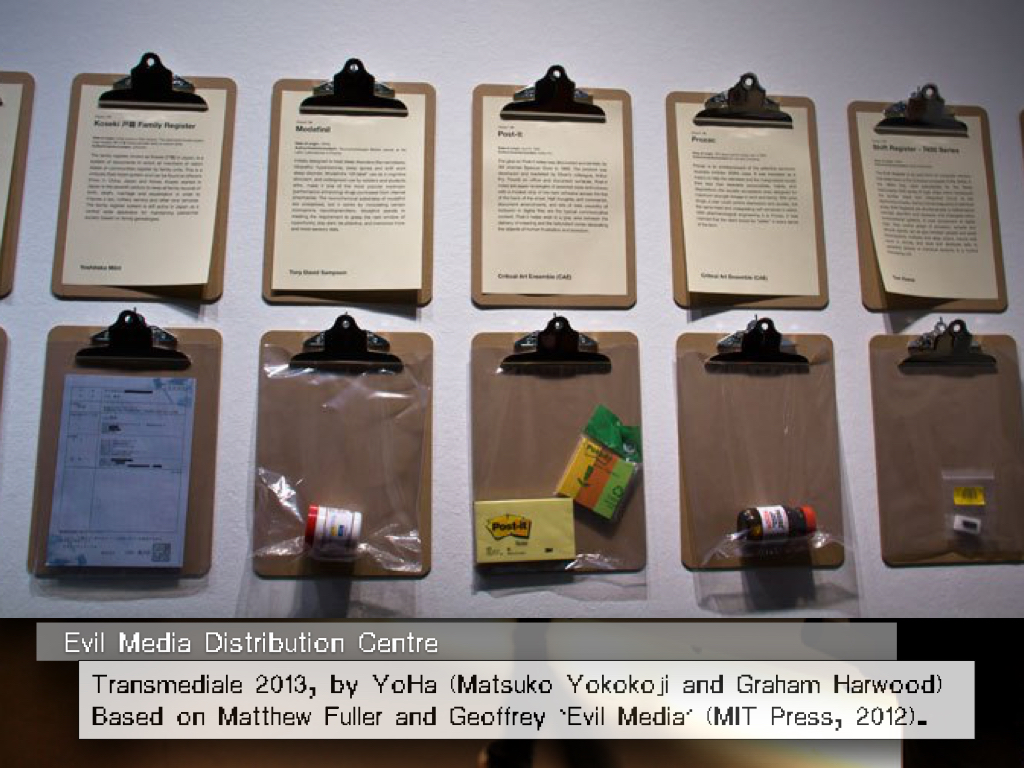

Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But I unfortunately, I kept quiet. In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahns writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise. This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness - it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: its the art of creative problem creation.In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of astranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016? The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic ofstrange that involves the with holding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex. The ellipses of mad logic (disfunctionality) is commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art. This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996),Glitch Art (±2001) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Notes

1. Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), p. 21.

2. On cool as ellipsis, Alan Liu. in The Laws of Cool. 2008.

3. “We need creative problem creation” - jonSatrom during GLI.TC/H 20111.

4. Within glitch art this subgenre is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art.

“Your work is so.. so weird…”

Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But I unfortunately, I kept quiet. In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahns writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise. This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness - it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: its the art of creative problem creation.In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of astranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016? The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic ofstrange that involves the with holding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex. The ellipses of mad logic (disfunctionality) is commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art. This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996),Glitch Art (±2001) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Notes

1. Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), p. 21.

2. On cool as ellipsis, Alan Liu. in The Laws of Cool. 2008.

3. “We need creative problem creation” - jonSatrom during GLI.TC/H 20111.

4. Within glitch art this subgenre is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art.