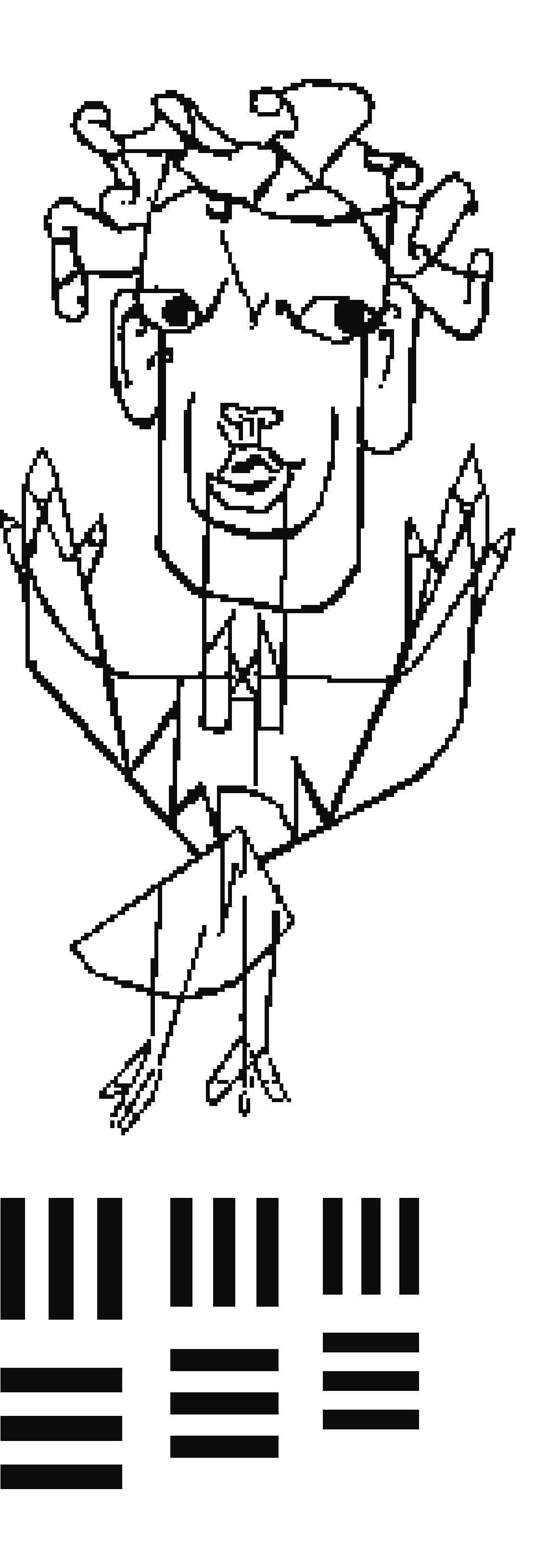

The Angel of History is the main protagonist in my artistic research.

Her journey through the realms of digital image processing is illustrated in Destitute Vision.

At the end of her journey, the Angel embraces her role as Media Archaeologist (from the future),

and compiles her insights on image infrastructure as Resolution Studies.

I think about the story of the Angel of History like this:

A myth functions like an algorithm; it encodes a worldview, specific to a time and place.

Recursively, algorithms can become myths: rewritten through updates, naturalized through use,

and rendered legible as cultural logic.

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎

Her journey through the realms of digital image processing is illustrated in Destitute Vision.

At the end of her journey, the Angel embraces her role as Media Archaeologist (from the future),

and compiles her insights on image infrastructure as Resolution Studies.

I think about the story of the Angel of History like this:

A myth functions like an algorithm; it encodes a worldview, specific to a time and place.

Recursively, algorithms can become myths: rewritten through updates, naturalized through use,

and rendered legible as cultural logic.

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎

INTRODUCTION TO RESOLUTION STUDIES

Why Study Resolutions?

Our (digital) image cultures are no longer just complex: they are confusing, contradictory, and increasingly illegible.

From deep fried to deep fake, and post-uncanny to neo-crapstraction, it is becoming harder to stay on top of the dialogue and grasp how, or what, is being imaged.

Is there a discourse, or is it all just instances?

Can I still connect to the contemporary dialogue?

What even is happening /now/?

In a landscape that features as many timelines as it has users, there is no singular ‘now’. Nor is there one truth: with constantly shifting perspectives on past and future, cause and effect have become unstable: they are fractured and delayed by platform logic and symbolic drift.

Because of this kludge of perspectives, the many decisions and compromises that shape our technological experiences remain obscure. We are often unaware of the rules and systems we activate. We see the outputs—rendered images and video content, their visibility ranked by attention or likes, but not the processes, infrastructures, trade-offs, and gatekeeping embedded in the systems that shape our experience.

We suffer from technological hyperopia: a mediated farsightedness.

We see what is rendered, but not how, or for whom. The same system may render a completely different image, version, or truth depending on algorithmic bias, user and context.

Resolution plays a key role in this procedural hyperopia. Often taken for granted as a number, or a default setting in a dropdown menu, it appears neutral. But behind these deceptively simple choices lie entire genealogies of technical, cultural, political, and economic decision-making.

The more complex the technology, the more invisible its compromises.

This is how resolution has become not just a technical setting, but a regime of rendering and a site of power.

Resolution Studies

Resolution is often misunderstood as a simple number; a quantitative or qualitative metric. But resolution is not a fixed technical specification. Resolution is a relational, procedural condition shaped by protocols, standards, infrastructures, and interpretive regimes.Morover, perceived quality of the image is relational too; it is shaped by how an image is captured, processed, circulated, and displayed. Acutance (edge contrast), for example, can enhance the perceptual clarity, even when no new detail is resolved. Distinctions within image quality, such as between acutance and resolvable detail (e.g., pixel count), reveal that sharpness itself is a constructed perceptual effect. Even an image with high spatial resolution may appear low quality on a screen with poor acutance, or after platform compression and algorithmic distortion.

Resolution is a procedural, context-dependent construct that emerges from the consolidation of multiple material systems. It is shaped not only at the point of capture, but also by the algorithms that compress, the platforms that render, and the interpretive frameworks in which images are received—ranging from sensor design to platform interface, and from standardized protocols to habituated use.

In this sense, resolution becomes a procedural attribute; an emergent property negotiated across infrastructures, institutions, and perceptual regimes.

Resolutions are further shaped by display technologies, compression pipelines, and viewing conditions. It may begin as a quantifying metric, but it becomes procedural—situated within the messy, evolving connections between technological systems and human perception.

Resolution Studies does not reject numerical definitions; rather, it repositions resolution as a process, situated within the intricacies of contemporary media environments. Here, it functions as a site of procedural opacity, where invisible constraints are naturalized as defaults, and the cost of adopting such standards is that we remain blind to the compromises they conceal.

Resolution Studies offers a theoretical and critical framework for interrogating these compromises. It examines both dominant and marginal forms of rendering visibility; not only in terms of spatial metrics but also in relation to genealogical, ethical, and epistemic dimensions. Drawing from protocol theory, tactical media, critical interface design, media archaeology, and epigraphy, it exposes how resolution governs what becomes visible—and what is left behind.

To study resolution is to study the biases embedded in standards: choices shaped by political, financial, and ideological pressures that determine not only what is rendered but what is excluded or forgotten. Standardized resolutions enforce order and efficiency, but they also obscure compromise and erase alternatives.

They black-box possibility.

Practice based research, art and theory

As an artist, I see it as my responsibility not only to engage critically with the materialities of the digital but to develop a fluid literacy of these constantly mutating infrastructures. If there is still meaning to the term new media, or the contemporary, it lies here: to develop a certain fluid literacy of these constantly developing and mutating material languages that impose constraints and qualities on the technologies we work with. To engage with digital culture today means to formulate a position, to understand what systems are being activated, and to speculate on what alternatives might still be possible. But this requires access and training; forms of literacy that are not equally distributed. Many tools we use offer no visibility into their underlying architectures, no access to their decision space.

Through this practice-based and theoretical research, I aim to uncover these speculative, anti-utopic, lost and unseen or simply "too good to be implemented" resolutions; to shed a light on the shadow side of resolutions. These might be illegible now, but they are not beyond recovery. What lies outside our current render framework is not necessarily impossible, it is just not yet implemented and unrealized. Resolution Studies allows us to articulate that shadow space. Whatever is not captured by our resolutions remains unseen, but it is not necessarily absent.

Finally, I believe that being an artist also means developing and sharing modes of thinking. That’s why all research and artworks I create remain freely available online, even after acquisition by an insitution.

I also try to publish all my syllabi, lectures, and papers (see below, embedded slides per page).

COPY <IT> RIGHT!

Resolution Studies

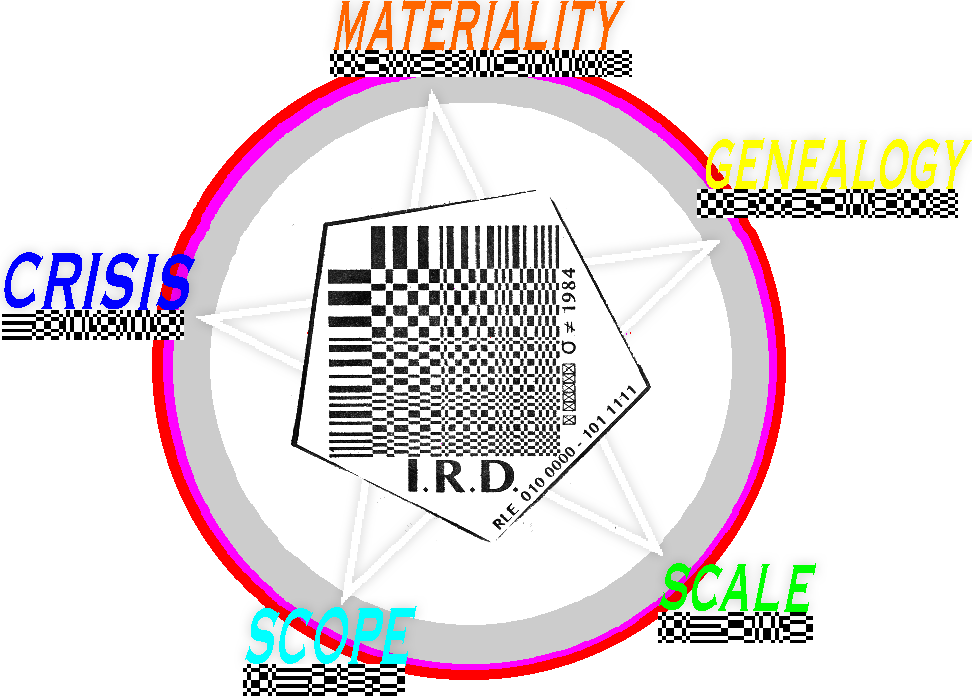

Resolution Studies is grounded in practical teaching and artistic research. It currently involves 5 “disputes,” each addressing a fundamental tension within the study of rendering, image culture, and media infrastructure:

>>> RESOLUTION STUDIES - for now - INVOLVES 7 CHAPTERS:

PRECONDITION 0000 : HOROLOGY

DISPUTE 0001 : MATERIALITY

HOW DATA, DECAY AND FORMAT SHAPE WHAT IS SEEN

DISPUTE 0010 : GENEALOGY

GENEALOGIES ENCODED IN STANDARDS

1. A GENEALOGY OF THE COLOUR TEST CARD

2. A GENEALOGY OF MACROBLOCK / FROM ARTIFACT TO A/EFFECT.

DISPUTE 0011 : SCOPE

HOW HABIT DELINEATES IM/POSSIBILITY AND IN/VISIBILITY

DISPUTE 0100 : SCALE

SCALING AS VIOLENCE

DISPUTE 0101 : CRISIS

THE ADDITIVE CRISIS OF THE IMAGE

0. THE OBSOLETE ANALOG IMAGE

1. TRANSITION FROM ANALOGUE TO DIGITAL

2. PLATFORMED IMAGE

3. CRISIS OF THE SYNTHETIC IMAGE

RENDER 0110 : ATLAS

Each dispute opens a terrain of theoretical and material exploration, inviting research and speculative practice.

>>> For a deeper theoretical framing, see this essay:Refuse to let the syntaxes of (a) history direct our futures. [PDF]

>>> And for a narrative conclusion, take a look at the crisis of the image at the end of Destitute Vision

Resolution Studies is grounded in practical teaching and artistic research. It currently involves 5 “disputes,” each addressing a fundamental tension within the study of rendering, image culture, and media infrastructure:

>>> RESOLUTION STUDIES - for now - INVOLVES 7 CHAPTERS:

PRECONDITION 0000 : HOROLOGY

DISPUTE 0001 : MATERIALITY

HOW DATA, DECAY AND FORMAT SHAPE WHAT IS SEEN

DISPUTE 0010 : GENEALOGY

GENEALOGIES ENCODED IN STANDARDS

1. A GENEALOGY OF THE COLOUR TEST CARD

2. A GENEALOGY OF MACROBLOCK / FROM ARTIFACT TO A/EFFECT.

DISPUTE 0011 : SCOPE

HOW HABIT DELINEATES IM/POSSIBILITY AND IN/VISIBILITY

DISPUTE 0100 : SCALE

SCALING AS VIOLENCE

DISPUTE 0101 : CRISIS

THE ADDITIVE CRISIS OF THE IMAGE

0. THE OBSOLETE ANALOG IMAGE

1. TRANSITION FROM ANALOGUE TO DIGITAL

2. PLATFORMED IMAGE

3. CRISIS OF THE SYNTHETIC IMAGE

RENDER 0110 : ATLAS

Each dispute opens a terrain of theoretical and material exploration, inviting research and speculative practice.

>>> For a deeper theoretical framing, see this essay:Refuse to let the syntaxes of (a) history direct our futures. [PDF]

>>> And for a narrative conclusion, take a look at the crisis of the image at the end of Destitute Vision

>>> PUBLICATIONS:

︎ Vernacular of File Formats (2010)

︎ Glitch Moment/um (INC: 2011)

︎ Beyond Resolution (i.R.D.: 2020)

︎ IM/POSSIBLE IMAGES READER (i.R.D.: 2022) HQ // LQ

︎ Whiteout

︎ Refuse to let the Syntaxes of (a) History Direct our Futures. In:Fragmentation of the Image (Routledge, 2019)

︎ MORE PUBLICATIONS HERE

>>> LECTURES, VIDEO ESSAYS AND ... VIDEO ART RESEARCH ESSAYS?!

︎ Refractions (2024-2025)

︎ A Spectrum of Lost and Unnamed Colours (2024)

︎ De/Calibration Target (2023)

︎ The Shredded Hologram Rose (2023)

︎ A Collection of Collections inside a Library for the INC (2023)

︎ Resolution Studies Lecture for MIT (2021)

︎ Destitute Vision Lecture for NCAD (2021)

︎ It takes more than the past to understand the archive Video essay for Stedelijk Studies (2020)

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎

Rosa Menkman is a Dutch artist and researcher of resolutions. Her work focuses on noise artifacts resulting from accidents in both analog and digital media.

The journey of her protagonist, the Angel of History—inspired by Paul Klee’s 1920 monoprint, Angelus Novus, and conceptualized by Walter Benjamin in 1940—functions as a foundational framework for her explorations of image processing technologies. As the machines upgrade, the Angel finds herself caught in the ripple of their distortions, unable to render the world around her.

Complementing her practice, she published Glitch Moment/um (INC, 2011), a book on the exploitation and popularization of glitch artifacts. She further explored the politics of image processing in Beyond Resolution (i.R.D., 2020). In this book, Rosa describes how the standardization of resolutions promotes efficiency, order, and functionality, but also involves compromises, resulting in the obfuscation of alternative ways of rendering.

In 2019, Menkman won the Collide Arts at CERN Barcelona award, which inspired her recent research into im/possible images, consolidated in the im/possible images reader (published by the i.R.D. & Lothringer, with support from V2, 2022).

From 2110 - 2112 the GLI.TC/H Bots facilitated a festival/gathering in Chicago, Amsterdam and Birmingham. Shoutouts to my fellow bots: Nick Briz, Jon Satrom, William Robertson and Antonio Roberts.

From 2018 to 2020, Menkman worked as Substitute Professor of Neue Medien & Visuelle Kommunikation at the Kunsthochschule Kassel. From 2023 - 2025 she ran the IM/POSSIBLE LAB at HEAD Geneve. Some class materials can be found here - please copy <it> right!.

Recent work can be found in this pdf portfolio.

The journey of her protagonist, the Angel of History—inspired by Paul Klee’s 1920 monoprint, Angelus Novus, and conceptualized by Walter Benjamin in 1940—functions as a foundational framework for her explorations of image processing technologies. As the machines upgrade, the Angel finds herself caught in the ripple of their distortions, unable to render the world around her.

Complementing her practice, she published Glitch Moment/um (INC, 2011), a book on the exploitation and popularization of glitch artifacts. She further explored the politics of image processing in Beyond Resolution (i.R.D., 2020). In this book, Rosa describes how the standardization of resolutions promotes efficiency, order, and functionality, but also involves compromises, resulting in the obfuscation of alternative ways of rendering.

In 2019, Menkman won the Collide Arts at CERN Barcelona award, which inspired her recent research into im/possible images, consolidated in the im/possible images reader (published by the i.R.D. & Lothringer, with support from V2, 2022).

From 2110 - 2112 the GLI.TC/H Bots facilitated a festival/gathering in Chicago, Amsterdam and Birmingham. Shoutouts to my fellow bots: Nick Briz, Jon Satrom, William Robertson and Antonio Roberts.

From 2018 to 2020, Menkman worked as Substitute Professor of Neue Medien & Visuelle Kommunikation at the Kunsthochschule Kassel. From 2023 - 2025 she ran the IM/POSSIBLE LAB at HEAD Geneve. Some class materials can be found here - please copy <it> right!

Recent work can be found in this pdf portfolio.

I believe in a Copy <it> Right ethic:

“First, it’s okay to copy! Believe in the process of copying as much as you can; with all your heart is a good place to start – get into it as straight and honestly as possible. Copying is as good (I think better from this vector-view) as any other way of getting ‚’there.’ ” – NOTES ON THE AESTHETICS OF ‘copying-an-Image Processor’ – Phil Morton (1973)

This means that copying as a creative, exploratory, and educational act is free and encouraged, provided proper accreditation is given. However, when copying transforms into commodification and profit is anticipated, explicit permission must be sought, and compensation may be requested.

“First, it’s okay to copy! Believe in the process of copying as much as you can; with all your heart is a good place to start – get into it as straight and honestly as possible. Copying is as good (I think better from this vector-view) as any other way of getting ‚’there.’ ” – NOTES ON THE AESTHETICS OF ‘copying-an-Image Processor’ – Phil Morton (1973)

This means that copying as a creative, exploratory, and educational act is free and encouraged, provided proper accreditation is given. However, when copying transforms into commodification and profit is anticipated, explicit permission must be sought, and compensation may be requested.

This website was made possible with the financial support from the Stimuleringsfonds.nl (2018)

I am grateful to have received a basis stipend from the Mondriaan Fund (2018-2021) and just recently: 2023 - 2026!

I am grateful to have received a basis stipend from the Mondriaan Fund (2018-2021) and just recently: 2023 - 2026!

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ ︎