GENEALOGY: GLITCH A/EFFECT

FROM ARTIFACT TO A/EFFECT

(OR: HOW GLITCH BECOMES AN INDEX FOR MEANING)

WRITTEN (THEORY)

>>> ALT.HISTORY FROM ARTIFACT TO EFFECT (2010 - ...)

>>> A stranger like Dada / Weird like quaint collage ¯_( ͡ఠʘᴥ ⊙ಥ‶ʔ)ノ/̵͇̿̿/̿ ̿ ̿☞ (2016)

>>> “We already know too much for noise to exist” (2016)

>>> LEXICON OF GLITCH AFFECT (2014)

(OR: HOW GLITCH BECOMES AN INDEX FOR MEANING)

WRITTEN (THEORY)

>>> ALT.HISTORY FROM ARTIFACT TO EFFECT (2010 - ...)

>>> A stranger like Dada / Weird like quaint collage ¯_( ͡ఠʘᴥ ⊙ಥ‶ʔ)ノ/̵͇̿̿/̿ ̿ ̿☞ (2016)

>>> “We already know too much for noise to exist” (2016)

>>> LEXICON OF GLITCH AFFECT (2014)

FROM ARTIFACT TO EFFECT

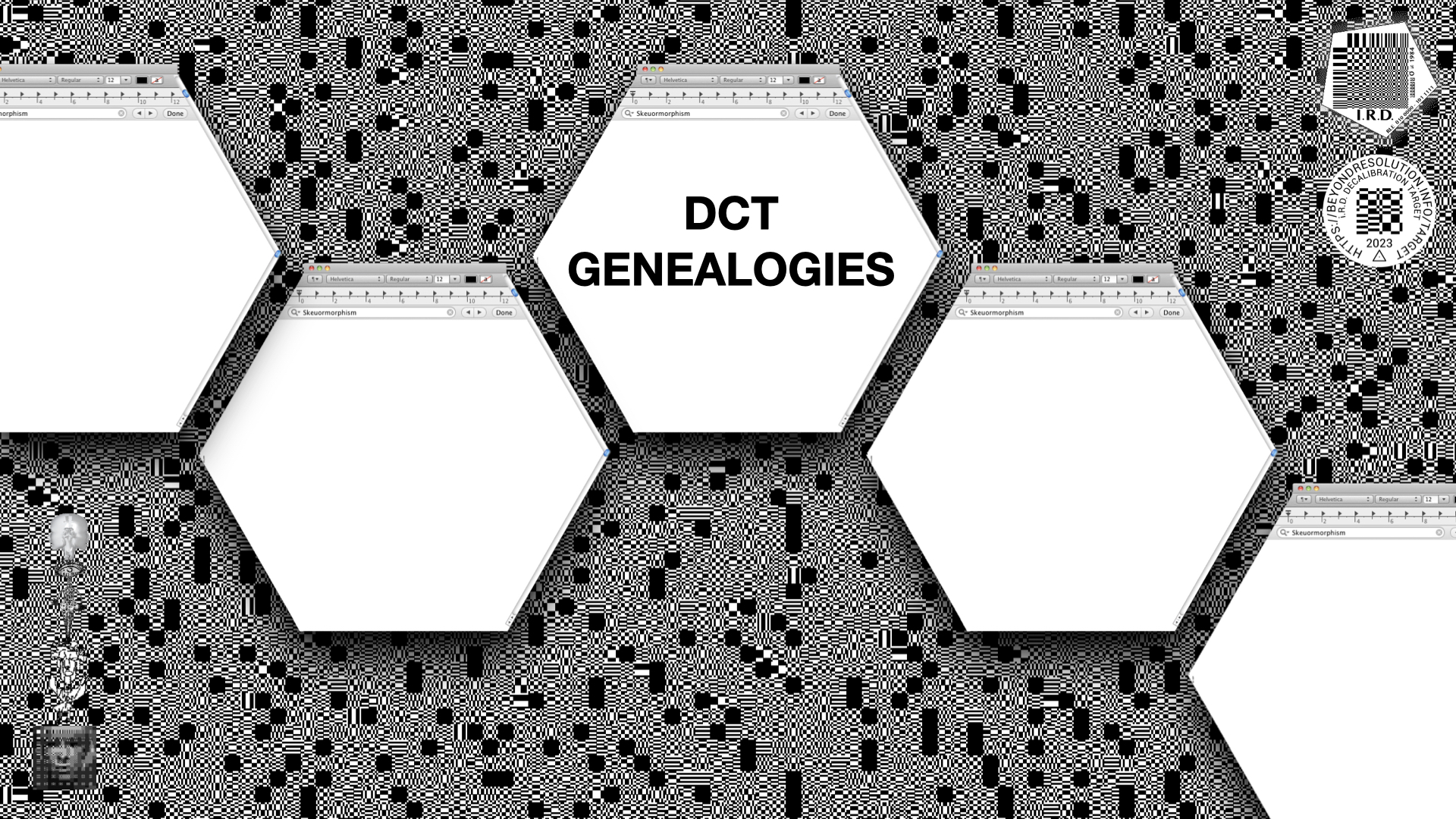

ALT.HISTORY (GENEALOGY OF MACROBLOCKS)

A stranger like Dada / Weird like quaint collage ¯_( ͡ఠʘᴥ ⊙ಥ‶ʔ)ノ/̵͇̿̿/̿ ̿ ̿☞

“Your work is so.. so weird…”

Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But I unfortunately, I kept quiet. In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahns writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise. This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness - it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: its the art of creative problem creation.In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of astranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016? The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic ofstrange that involves the with holding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex. The ellipses of mad logic (disfunctionality) is commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art. This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996),Glitch Art (±2001) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Notes

1. Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), p. 21.

2. On cool as ellipsis, Alan Liu. in The Laws of Cool. 2008.

3. “We need creative problem creation” - jonSatrom during GLI.TC/H 20111.

4. Within glitch art this subgenre is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art.

“Your work is so.. so weird…”

Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But I unfortunately, I kept quiet. In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahns writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise. This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness - it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: its the art of creative problem creation.In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of astranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016? The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic ofstrange that involves the with holding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex. The ellipses of mad logic (disfunctionality) is commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art. This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996),Glitch Art (±2001) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Notes

1. Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), p. 21.

2. On cool as ellipsis, Alan Liu. in The Laws of Cool. 2008.

3. “We need creative problem creation” - jonSatrom during GLI.TC/H 20111.

4. Within glitch art this subgenre is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art.

“We already know too much for noise to exist”

- Douglas Kahn, Noise Water Meat: 1999 (p. 21)

As the popularization and cultivation of glitch artifacts is spreading, it is interesting to track the development of these processes in specific case studies. One case study of a compression artifact, referred to as ‘datamoshing’, tells an especially interesting account of glitch cultivation.

The datamosh artifact is located in a realm where compression artifacts and glitch artifacts collide. The artifact caused by compression is stable and reproducible, as it is the effective outcome of keyframes being deleted. The outcome of this deletion is the visualisation of the indexed movement of macroblocks, smearing over the surface of an old keyframe. This makes the video morph in unexpected colours and forms.

In 2005, Sven König embarked on his exploration into the politics of file standards, through this particular datamoshing effect, and in relation to the free codec Xvid. Xvid is a primary competitor of the proprietary DivX Pro Codec (note that Xvid is DivX spelled backwards), which is often used for speedy online video distribution through peer-to-peer networks. In aPpRoPiRaTe! (Sweden: 2005) König used the codec to manipulate and appropriate ‘complete video files found in file sharing networks’. His work included an open source software script that could be used to trigger the compression-effect in realtime. Through the use of the Xvid codec and copyrighted material, König tried to pinpoint the tension between the usage of non-proprietary compression codecs and their uptake in DRM (Digital Rights Management) remix-strategies.

In his next project, Download Finished! (2007), König explored how the codec could be used to transform and republish found footage from p2p networks and online archives. The result became the rough material for his online transformation software, which translated ‘the underlying data structures of the films onto the surface of the screen’. With the help of the software, file sharers could become ‘authors by re-interpreting their most beloved films’.

A swift maturation of the datamoshing effect took place in 2009 at the same time as Paul B. Davis was preparing for his solo show at the Seventeen Gallery in London. Davis’ show was partially based on a formal and aesthetic exploration of the artifact. While the show was intended to critique popular culture by way of datamosh interventions, this culture caught up with him overnight, when the effect penetrated the mainstream just prior to the opening of his show. Davis’ reaction to the fate of appropriation plays out as the opening quote of this chapter: ‘It fucked my show up...the very language I was using to critique pop content from the outside was now itself a mainstream cultural reference’.

Prominent music videos, including Kanye West’s Welcome To Heartbreak (2009, directed by Nabil Elderkin) and Chairlift’s Evident Utensil (2009, Ray Tintori) indeed had popped up bringing the datamoshing effect into the mainstream via MTV. The new wave of interest in the effect generated by these clips, lead to a Youtube tutorial on datamoshing, followed by an explosion of datamosh videos and the creation of different datamosh plugins, developed by for instance the Japanese artist UCNV, the director of the Evident Utensil Video Bob Weisz or Goldmosh Sam Goldstein.

In the 2010 GLI.TC/H festival in Chicago, thirty percent of the entries were based on the datamoshing technique (around 80 of a total 240). The technique that was used to critique popular culture, by artists like König or Davis, was now used to generate live visuals for the masses. Datamoshing had become a controlled, consumed and established effect. The aesthetic institutionalization of the datamoshing artifact became more evident when Murata’s video art work Monster Movie (2005), which used datamoshing as a form of animation, entered the Museum of Modern Art in New York in an exhibition in 2010.

This ‘new’ form of conservative glitch art puts an emphasis on design and end products, rather than on the post-procedural and political breaking of flows. There is an obvious critique here: to design a glitch means to domesticate it. When the glitch becomes domesticated into a desired process, controlled by a tool, or technology - essentially cultivated - it has lost the radical basis of its enchantment and becomes predictable. It is no longer a break from a flow within a technology, but instead a form of craft. For many critical artists, it is considered no longer a glitch, but a filter that consists of a preset and/or a default: what was once a glitch is now a new commodity.

- Douglas Kahn, Noise Water Meat: 1999 (p. 21)

As the popularization and cultivation of glitch artifacts is spreading, it is interesting to track the development of these processes in specific case studies. One case study of a compression artifact, referred to as ‘datamoshing’, tells an especially interesting account of glitch cultivation.

The datamosh artifact is located in a realm where compression artifacts and glitch artifacts collide. The artifact caused by compression is stable and reproducible, as it is the effective outcome of keyframes being deleted. The outcome of this deletion is the visualisation of the indexed movement of macroblocks, smearing over the surface of an old keyframe. This makes the video morph in unexpected colours and forms.

In 2005, Sven König embarked on his exploration into the politics of file standards, through this particular datamoshing effect, and in relation to the free codec Xvid. Xvid is a primary competitor of the proprietary DivX Pro Codec (note that Xvid is DivX spelled backwards), which is often used for speedy online video distribution through peer-to-peer networks. In aPpRoPiRaTe! (Sweden: 2005) König used the codec to manipulate and appropriate ‘complete video files found in file sharing networks’. His work included an open source software script that could be used to trigger the compression-effect in realtime. Through the use of the Xvid codec and copyrighted material, König tried to pinpoint the tension between the usage of non-proprietary compression codecs and their uptake in DRM (Digital Rights Management) remix-strategies.

In his next project, Download Finished! (2007), König explored how the codec could be used to transform and republish found footage from p2p networks and online archives. The result became the rough material for his online transformation software, which translated ‘the underlying data structures of the films onto the surface of the screen’. With the help of the software, file sharers could become ‘authors by re-interpreting their most beloved films’.

A swift maturation of the datamoshing effect took place in 2009 at the same time as Paul B. Davis was preparing for his solo show at the Seventeen Gallery in London. Davis’ show was partially based on a formal and aesthetic exploration of the artifact. While the show was intended to critique popular culture by way of datamosh interventions, this culture caught up with him overnight, when the effect penetrated the mainstream just prior to the opening of his show. Davis’ reaction to the fate of appropriation plays out as the opening quote of this chapter: ‘It fucked my show up...the very language I was using to critique pop content from the outside was now itself a mainstream cultural reference’.

Prominent music videos, including Kanye West’s Welcome To Heartbreak (2009, directed by Nabil Elderkin) and Chairlift’s Evident Utensil (2009, Ray Tintori) indeed had popped up bringing the datamoshing effect into the mainstream via MTV. The new wave of interest in the effect generated by these clips, lead to a Youtube tutorial on datamoshing, followed by an explosion of datamosh videos and the creation of different datamosh plugins, developed by for instance the Japanese artist UCNV, the director of the Evident Utensil Video Bob Weisz or Goldmosh Sam Goldstein.

In the 2010 GLI.TC/H festival in Chicago, thirty percent of the entries were based on the datamoshing technique (around 80 of a total 240). The technique that was used to critique popular culture, by artists like König or Davis, was now used to generate live visuals for the masses. Datamoshing had become a controlled, consumed and established effect. The aesthetic institutionalization of the datamoshing artifact became more evident when Murata’s video art work Monster Movie (2005), which used datamoshing as a form of animation, entered the Museum of Modern Art in New York in an exhibition in 2010.

This ‘new’ form of conservative glitch art puts an emphasis on design and end products, rather than on the post-procedural and political breaking of flows. There is an obvious critique here: to design a glitch means to domesticate it. When the glitch becomes domesticated into a desired process, controlled by a tool, or technology - essentially cultivated - it has lost the radical basis of its enchantment and becomes predictable. It is no longer a break from a flow within a technology, but instead a form of craft. For many critical artists, it is considered no longer a glitch, but a filter that consists of a preset and/or a default: what was once a glitch is now a new commodity.

Over the past decennia, the glitch art genre has grown up so much: glitch (and glitch art) is not just an aesthetic in digital art, glitch is in the world now.

I wrote the Glitch Moment(um) a little over 10 years ago. A main point then was that every form of glitch, either accidental or designed, will eventually become a new form or even a meaningful expression. Since then, digital technologies have reinforced their ubiquitous and pervasive presence. And with their ubiquity, artefacts such as cracked screens, broken images, colour channel shifts and other form of noise have become every day occurrences. In fact, everything seems to be littered with glitch. Glitches are on the flyer of my local falafel shop. They are in the commercials of my least favourite politicians. I can even deploy different types of glitches as a face filter on instagram. As a result, glitches have moved far away from being just a scary, or unexpected break; they are no longer just a moment of digital interruption - a moment when what lies ahead is unknown. The glitch is in the world now, not just as a digital event but also as a meaningful signifier; a figure of speech or a metaphor, with its own dialect and syntax. Just think about how in the movies, ghosts still announce their presence by adding analogue noise to a digital signals, or how blocky artifacts often signify a camera travelling through time. How lines and interlacing often describe an alien compromise of our telecommunication systems and how hackers still work in monochrome, green environments.

From its beginnings, glitch art used to exploit medium-reflexivity, to rhetorically question a ‘perfect’ use, or technological conventions and expectations. Artists adopted the glitch as a tool to question how computation shapes our everyday life. But today, distortions prompt the spectator to engage not only with the technology itself, but also with complex subcultural and meta-cultural narratives and gestures, presenting new analytical challenges. In short, the role of glitch in our daily lives has evolved and the glitch art genre has grown up.

But besides re-evaluating the study of glitch as a carrier of meaning, the glitch, or the digital accident, has also evolved on a fundamental level; in timing and space. Due to the networked nature of digital technologies, digital accidents are now decentralised; their cause and effects ripple through platforms, while the timing of these accident is no longer linear. The glitch no longer takes place as a linear sequence of events (interruption - glitch - debugging or collapse); and its interruptions do not happen momentarily, but instead as randomly timed pings inviting collapse or complexity anywhere the network reaches.

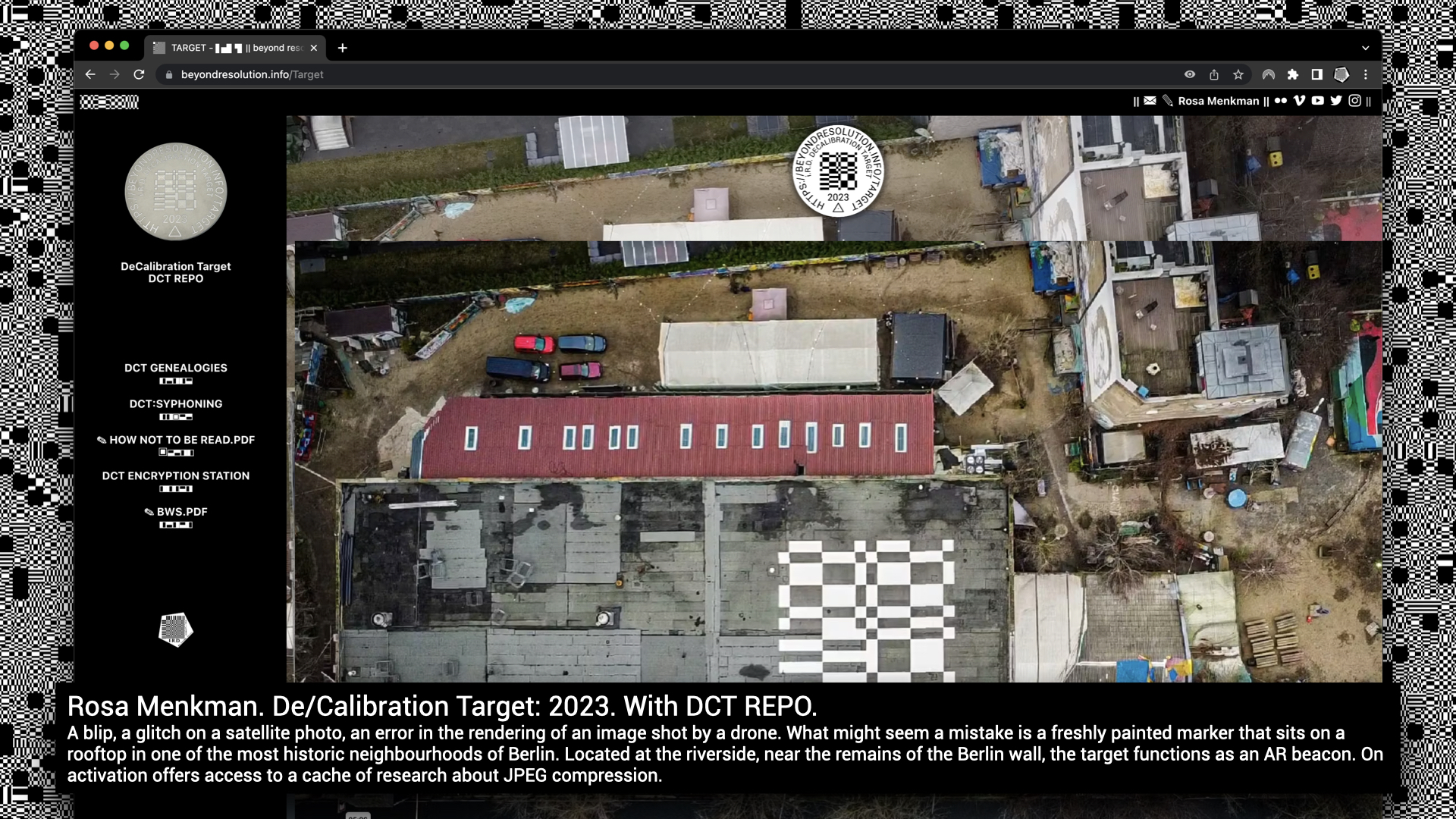

On the flip side, while the dominant, continuing search for a noiseless channel is still a regrettable, ill-fated dogma, we are filtering, suppressing and dismissing noise and glitch more widely than ever. As a result of this insight, I recently shifted my research to Resolution Studies. In a small new book, titled Beyond Resolution (2021), I describe the standardization of resolutions as a process that generally imposes efficiency, order and functionality on our technologies. But I also write that resolutions do not just involve the creation of protocols and solutions. They also entail the obfuscation of compromise and black-boxing of alternative possibilities, which as a result, are in danger of staying forever unseen or even forgotten. In this new book I deploy the glitch as a tool, for visiting and re-evaluating these compromises. I have experienced that while the glitch has evolved and changed, the glitch is still as powerful as a decade ago.

Glitch Art genre

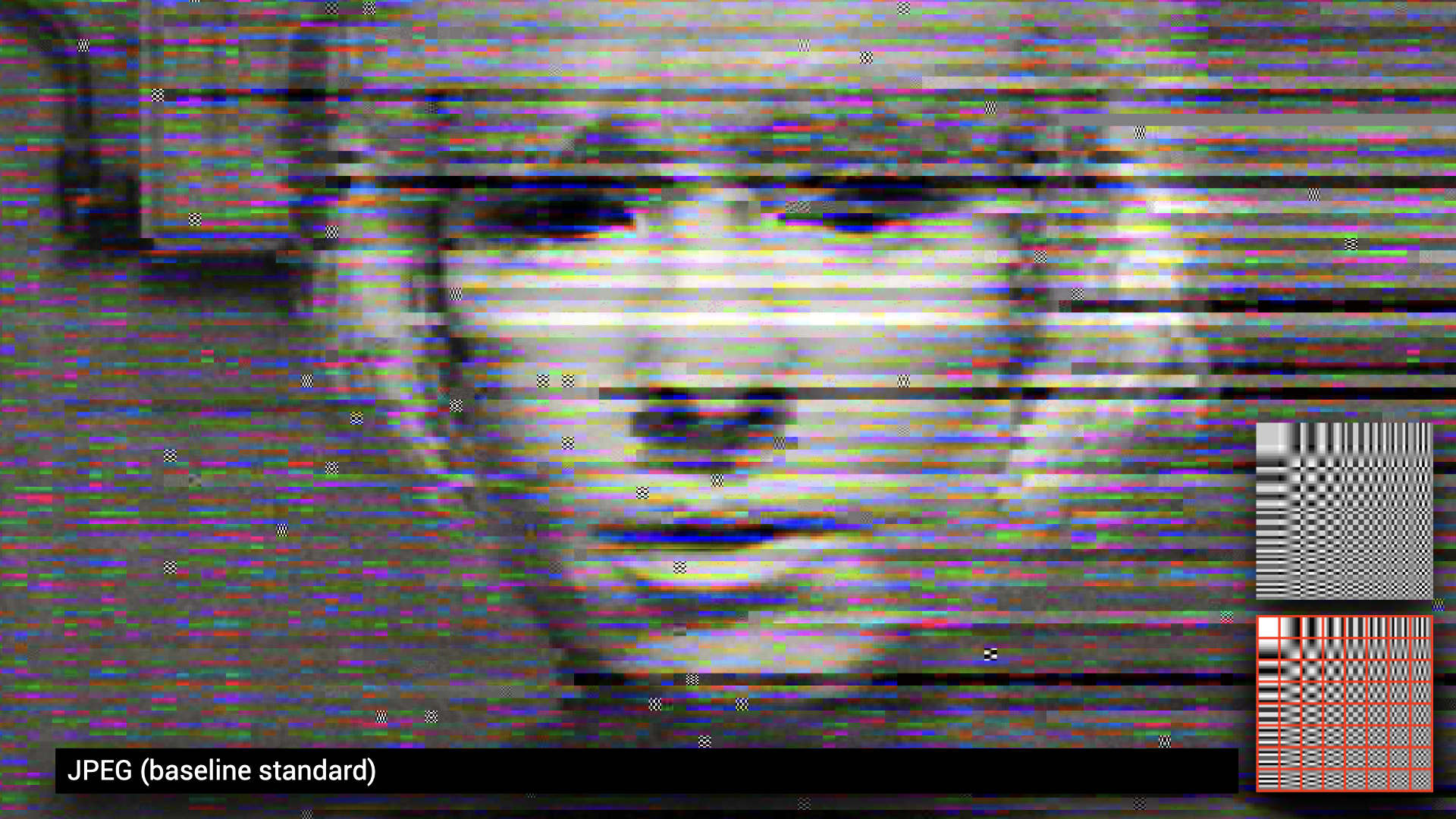

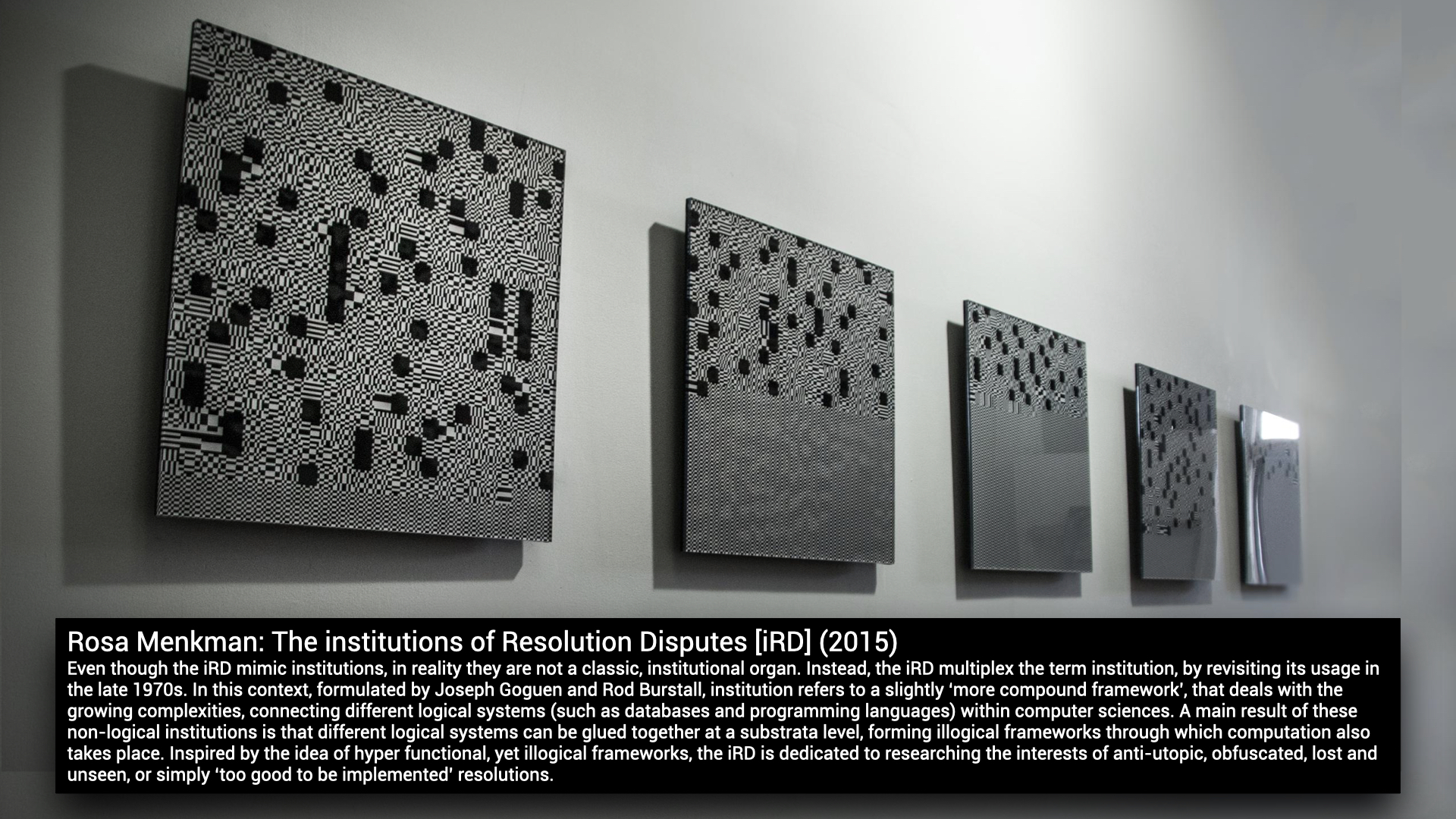

As the popularization and cultivation of the glitch genre has now spread widely, I believe it is important to track the development of these processes in specific case studies and create ‘a lexicon of distortions’. New, fresh research within the field of noise artifacts is necessary. In an attempt to expand on A Vernacular of File Formats, I propose a lexicon that deconstructs the meanings of noise artifacts; a handbook to navigate glitch clichés as employed specifically in the genre of Sci-Fi.

This Lexicon intends to offer an insight into the development of meaning in the aesthetics of distortion in Sci-Fi movies throughout the years, via an analysis of 1200 Sci-Fi Trailers. Starting with trailers from 1998, I reviewed 30 trailers per year to obtain an insight into the development of noise artifacts in Sci-Fi from before the normalization of the home computer, to Sci-Fi adopting the contemporary aesthetics of our ubiquitous digital devices. My source for the trailers is the Internet Movie Database, where I accessed lists of the top-US Grossing Sci-Fi Titles per year. When watching these trailers I took screenshots whenever a distortion occured. Then, if possible, I would interpret them. Currently the database includes findings from research done into 630 trailers (1998-2018) but I wish to extend it to 1980-2020, spanning the 40 years of advancements in digital technologies and its distortions.

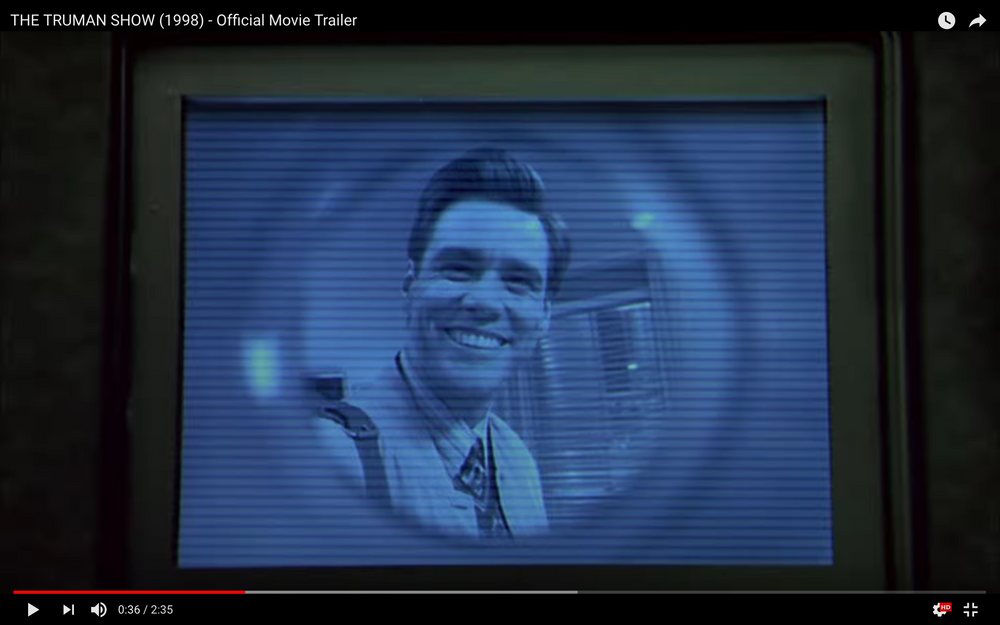

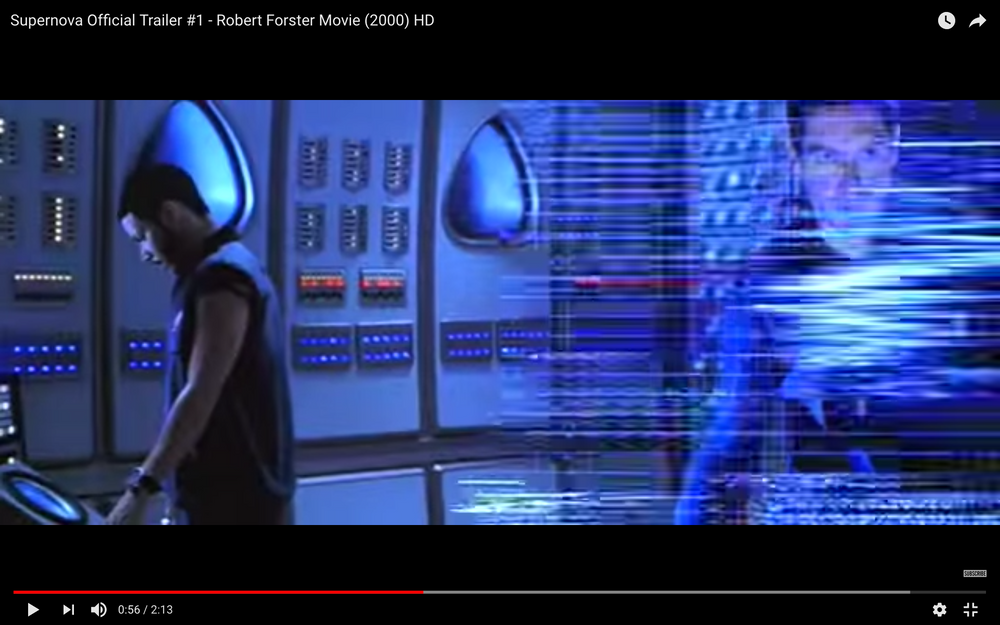

Sci-Fi relies on the literacy of the spectator (references to media technology texts, aesthetics and machinic processes) and their knowledge of more ‘conventional’ distortion or noise artifacts. Former disturbances have gained complex meaning beyond their technological value; with the help of popular culture, these effects have transformed into signifiers provoking affect. For example, analogue noise conjures up the sense of an eerie, invisible power entering the frame (a ghost), while blocky-artifacts often refer to time travelling or a data offense initiated by an Artificial Intelligence. Interlacing refers to an invisible camera, while camera interface esthetics (such as a viewfinders and tracking brackets or markers around a face) refer to observation technologies. Hackers still work in monochrome, green environments, while all holograms are made from phosphorous blue light. And when color channels distort, the protagonist is experiencing a loss of control.

︎Click on a year and see all the a/effect per trailer of that year!

I wrote the Glitch Moment(um) a little over 10 years ago. A main point then was that every form of glitch, either accidental or designed, will eventually become a new form or even a meaningful expression. Since then, digital technologies have reinforced their ubiquitous and pervasive presence. And with their ubiquity, artefacts such as cracked screens, broken images, colour channel shifts and other form of noise have become every day occurrences. In fact, everything seems to be littered with glitch. Glitches are on the flyer of my local falafel shop. They are in the commercials of my least favourite politicians. I can even deploy different types of glitches as a face filter on instagram. As a result, glitches have moved far away from being just a scary, or unexpected break; they are no longer just a moment of digital interruption - a moment when what lies ahead is unknown. The glitch is in the world now, not just as a digital event but also as a meaningful signifier; a figure of speech or a metaphor, with its own dialect and syntax. Just think about how in the movies, ghosts still announce their presence by adding analogue noise to a digital signals, or how blocky artifacts often signify a camera travelling through time. How lines and interlacing often describe an alien compromise of our telecommunication systems and how hackers still work in monochrome, green environments.

From its beginnings, glitch art used to exploit medium-reflexivity, to rhetorically question a ‘perfect’ use, or technological conventions and expectations. Artists adopted the glitch as a tool to question how computation shapes our everyday life. But today, distortions prompt the spectator to engage not only with the technology itself, but also with complex subcultural and meta-cultural narratives and gestures, presenting new analytical challenges. In short, the role of glitch in our daily lives has evolved and the glitch art genre has grown up.

But besides re-evaluating the study of glitch as a carrier of meaning, the glitch, or the digital accident, has also evolved on a fundamental level; in timing and space. Due to the networked nature of digital technologies, digital accidents are now decentralised; their cause and effects ripple through platforms, while the timing of these accident is no longer linear. The glitch no longer takes place as a linear sequence of events (interruption - glitch - debugging or collapse); and its interruptions do not happen momentarily, but instead as randomly timed pings inviting collapse or complexity anywhere the network reaches.

On the flip side, while the dominant, continuing search for a noiseless channel is still a regrettable, ill-fated dogma, we are filtering, suppressing and dismissing noise and glitch more widely than ever. As a result of this insight, I recently shifted my research to Resolution Studies. In a small new book, titled Beyond Resolution (2021), I describe the standardization of resolutions as a process that generally imposes efficiency, order and functionality on our technologies. But I also write that resolutions do not just involve the creation of protocols and solutions. They also entail the obfuscation of compromise and black-boxing of alternative possibilities, which as a result, are in danger of staying forever unseen or even forgotten. In this new book I deploy the glitch as a tool, for visiting and re-evaluating these compromises. I have experienced that while the glitch has evolved and changed, the glitch is still as powerful as a decade ago.

Glitch Art genre

As the popularization and cultivation of the glitch genre has now spread widely, I believe it is important to track the development of these processes in specific case studies and create ‘a lexicon of distortions’. New, fresh research within the field of noise artifacts is necessary. In an attempt to expand on A Vernacular of File Formats, I propose a lexicon that deconstructs the meanings of noise artifacts; a handbook to navigate glitch clichés as employed specifically in the genre of Sci-Fi.

This Lexicon intends to offer an insight into the development of meaning in the aesthetics of distortion in Sci-Fi movies throughout the years, via an analysis of 1200 Sci-Fi Trailers. Starting with trailers from 1998, I reviewed 30 trailers per year to obtain an insight into the development of noise artifacts in Sci-Fi from before the normalization of the home computer, to Sci-Fi adopting the contemporary aesthetics of our ubiquitous digital devices. My source for the trailers is the Internet Movie Database, where I accessed lists of the top-US Grossing Sci-Fi Titles per year. When watching these trailers I took screenshots whenever a distortion occured. Then, if possible, I would interpret them. Currently the database includes findings from research done into 630 trailers (1998-2018) but I wish to extend it to 1980-2020, spanning the 40 years of advancements in digital technologies and its distortions.

Sci-Fi relies on the literacy of the spectator (references to media technology texts, aesthetics and machinic processes) and their knowledge of more ‘conventional’ distortion or noise artifacts. Former disturbances have gained complex meaning beyond their technological value; with the help of popular culture, these effects have transformed into signifiers provoking affect. For example, analogue noise conjures up the sense of an eerie, invisible power entering the frame (a ghost), while blocky-artifacts often refer to time travelling or a data offense initiated by an Artificial Intelligence. Interlacing refers to an invisible camera, while camera interface esthetics (such as a viewfinders and tracking brackets or markers around a face) refer to observation technologies. Hackers still work in monochrome, green environments, while all holograms are made from phosphorous blue light. And when color channels distort, the protagonist is experiencing a loss of control.

︎Click on a year and see all the a/effect per trailer of that year!

1998 - In the Truman Show, CCTVs secret observation cameras are outfitted with scanlines and vignetting.

1998 - In the Truman Show, CCTVs secret observation cameras are outfitted with scanlines and vignetting. 1999 - Unicode characters displayed as streams of monochrome, vertical data signify the hackers navigating ‘the Matrix’.

1999 - Unicode characters displayed as streams of monochrome, vertical data signify the hackers navigating ‘the Matrix’. 2000 - Sci fi screens feature a lot of blue because sets often use tungsten (warm) light. Filmmakers compensate for this in post processing, during which blue colors are effected the least, maintaining the vibrancy of other colors the best.

In this shot from Supernova, a critical SOS signal is received.

2000 - Sci fi screens feature a lot of blue because sets often use tungsten (warm) light. Filmmakers compensate for this in post processing, during which blue colors are effected the least, maintaining the vibrancy of other colors the best.

In this shot from Supernova, a critical SOS signal is received.

2001 - in Jimmy Neutron, an alien observes the parents. A voice over says: “The crummy aliens stole our parents”

2001 - in Jimmy Neutron, an alien observes the parents. A voice over says: “The crummy aliens stole our parents”

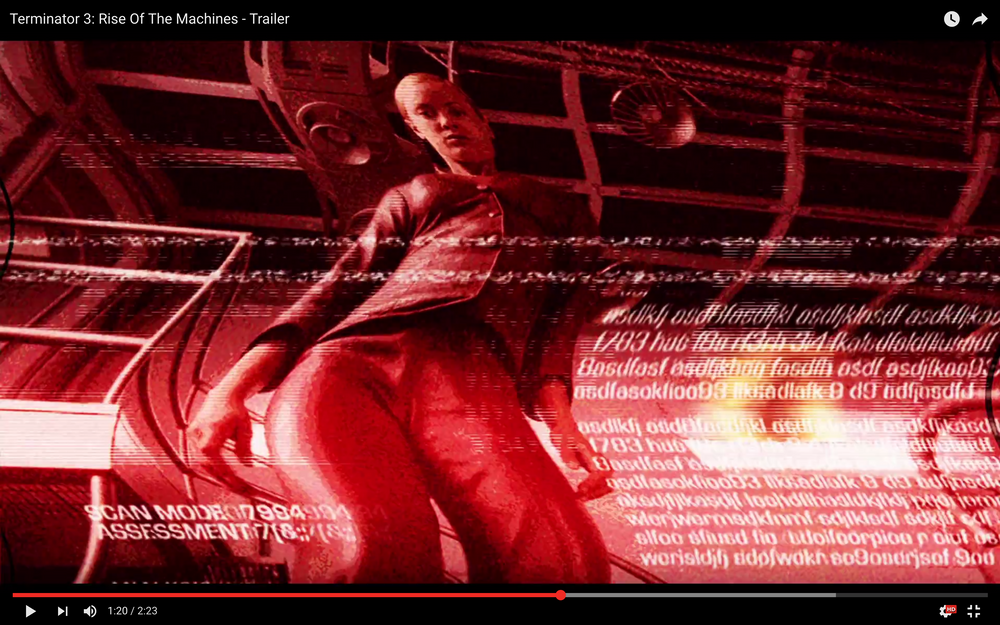

2003 - “The machines are starting to take over!” is uttered when T-X knocks out the terminator. A combination of what seems like digital and analogue, monochrome red distortions cover the ‘interface’ of the Terminators point of view as he goes down.

2003 - “The machines are starting to take over!” is uttered when T-X knocks out the terminator. A combination of what seems like digital and analogue, monochrome red distortions cover the ‘interface’ of the Terminators point of view as he goes down.  2004 - In The Manchurian Candidate, soldiers are kidnapped and brainwashed for sinister purposes. Some of the shots use military night vision equiplement.

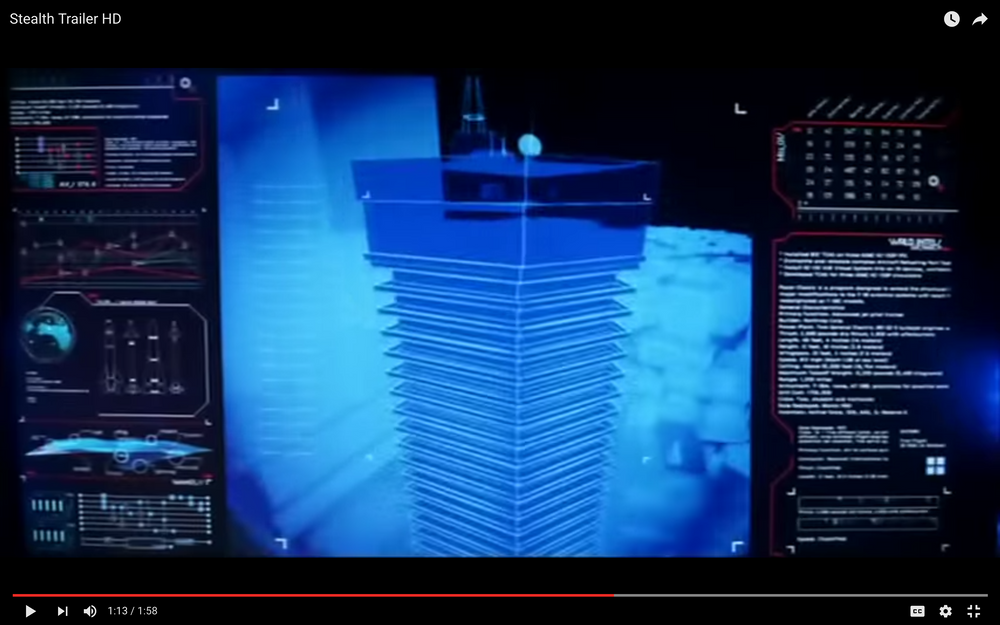

2004 - In The Manchurian Candidate, soldiers are kidnapped and brainwashed for sinister purposes. Some of the shots use military night vision equiplement.  2005 - In Stealth, an artificial intelligence program has “rewired itself and chosen its own target”. Blue, phosphorous holograms are flanked by non understandable diagrams and information.

2005 - In Stealth, an artificial intelligence program has “rewired itself and chosen its own target”. Blue, phosphorous holograms are flanked by non understandable diagrams and information.  2006 -

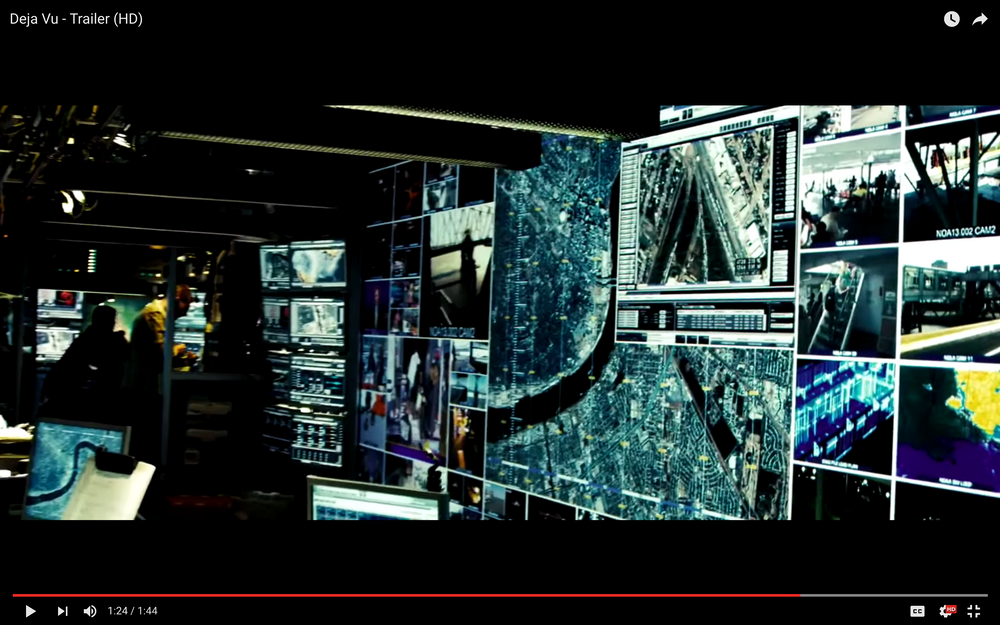

‘experimental surveillance technology’ uses grid like, monochrome maps on top of maps in Deja Vu

2006 -

‘experimental surveillance technology’ uses grid like, monochrome maps on top of maps in Deja Vu 2007 - Umbrella Corp uses surveillance technology, which uses tracking brackets and facial markers to compare a target to an image file.

2007 - Umbrella Corp uses surveillance technology, which uses tracking brackets and facial markers to compare a target to an image file.

2008 - Interruptions in live television streams are no longer illustrated by analogue noise, but by macroblocking artifacts (referencing new .mp4 and streaming technologies) in Quarantine.

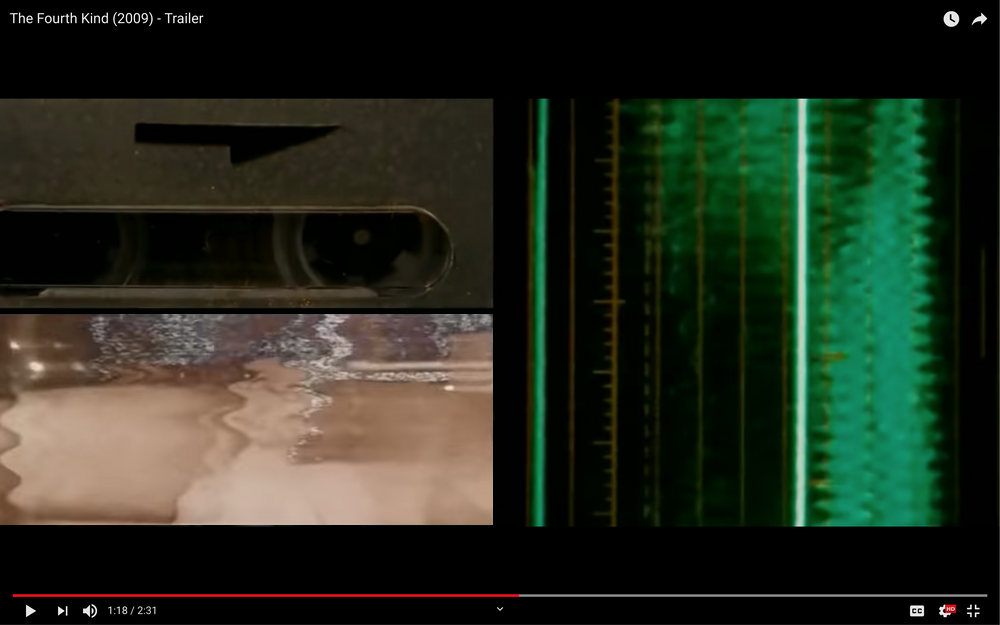

2008 - Interruptions in live television streams are no longer illustrated by analogue noise, but by macroblocking artifacts (referencing new .mp4 and streaming technologies) in Quarantine.  2009 - A fantastic year for glitch artifacts in sci fi, my favorite trailer is the Fourth Kind, which features monchrome EVP alongside analogue, wobbulating video registrations.

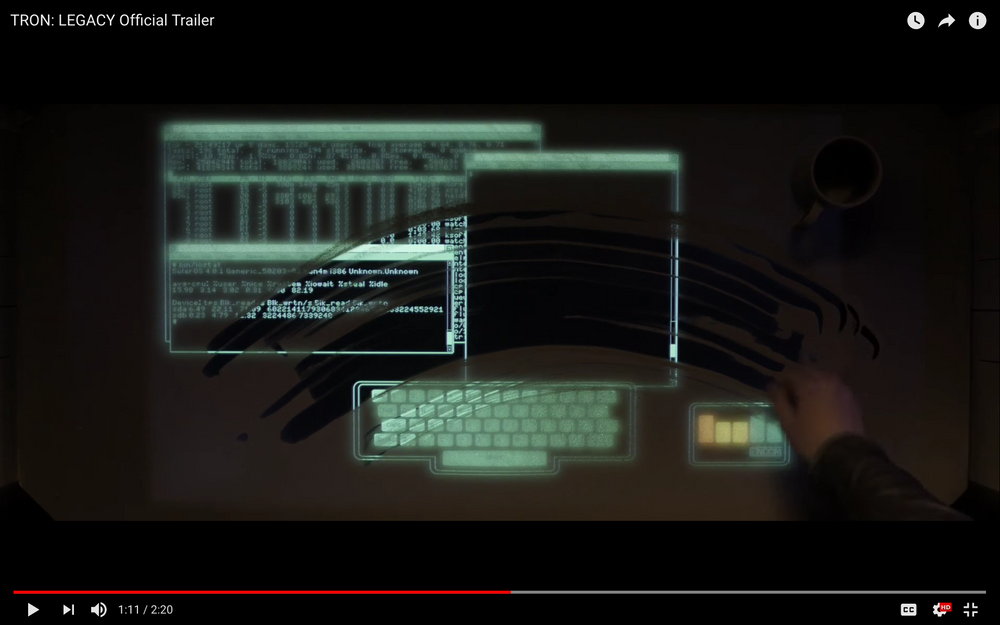

2009 - A fantastic year for glitch artifacts in sci fi, my favorite trailer is the Fourth Kind, which features monchrome EVP alongside analogue, wobbulating video registrations. 2010 - The good old text based, cyano green (old and hacker) console that functions as a portal to Tron.

2010 - The good old text based, cyano green (old and hacker) console that functions as a portal to Tron.  2011 - In Source code, a soldier can not only jump back in time but also into someone else's body. These jumps are always rough and confusing. Aesthetically, the jump look a body fell apart into little triangular vectors travelling a somewhat noisy, blocky [that must be the time shift] wire plane.

2011 - In Source code, a soldier can not only jump back in time but also into someone else's body. These jumps are always rough and confusing. Aesthetically, the jump look a body fell apart into little triangular vectors travelling a somewhat noisy, blocky [that must be the time shift] wire plane.

2012 - Looper is set in 2074. In this time, when the mob wants to get rid of someone, the target is sent into the past, where a hired gun awaits. Time jump problems are shown by a sliced image with ghosting colors.

2012 - Looper is set in 2074. In this time, when the mob wants to get rid of someone, the target is sent into the past, where a hired gun awaits. Time jump problems are shown by a sliced image with ghosting colors.  2013 - In Elysium, Max is observed through a broken monitor. It is so action packed, even the color channels are no longer properly aligned.

2013 - In Elysium, Max is observed through a broken monitor. It is so action packed, even the color channels are no longer properly aligned.  2014 - During a fighting scene between Electro, who has the ability to control electricity, and Spiderman, the billboards of Times Square go all glitchy. ÷ The Amazing Spider-Man™ 2 (2014) was shot on KODAK VISION3 Color Negative Film.

2014 - During a fighting scene between Electro, who has the ability to control electricity, and Spiderman, the billboards of Times Square go all glitchy. ÷ The Amazing Spider-Man™ 2 (2014) was shot on KODAK VISION3 Color Negative Film.

All the bill boards glitch and finally explode, while Kodak is the of the last billboards left standing.

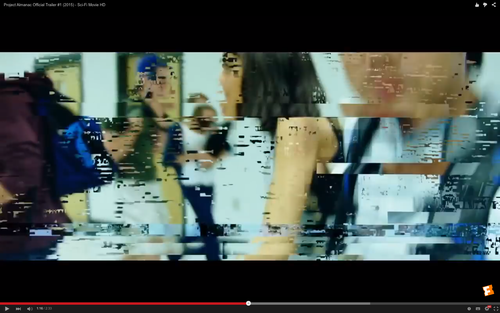

2015 - A group of teens discover secret plans of a time machine, and construct one. However, things start to get out of control. This is when blocking artifacts occur (similar to DV blocking when a tape is being FFWD).

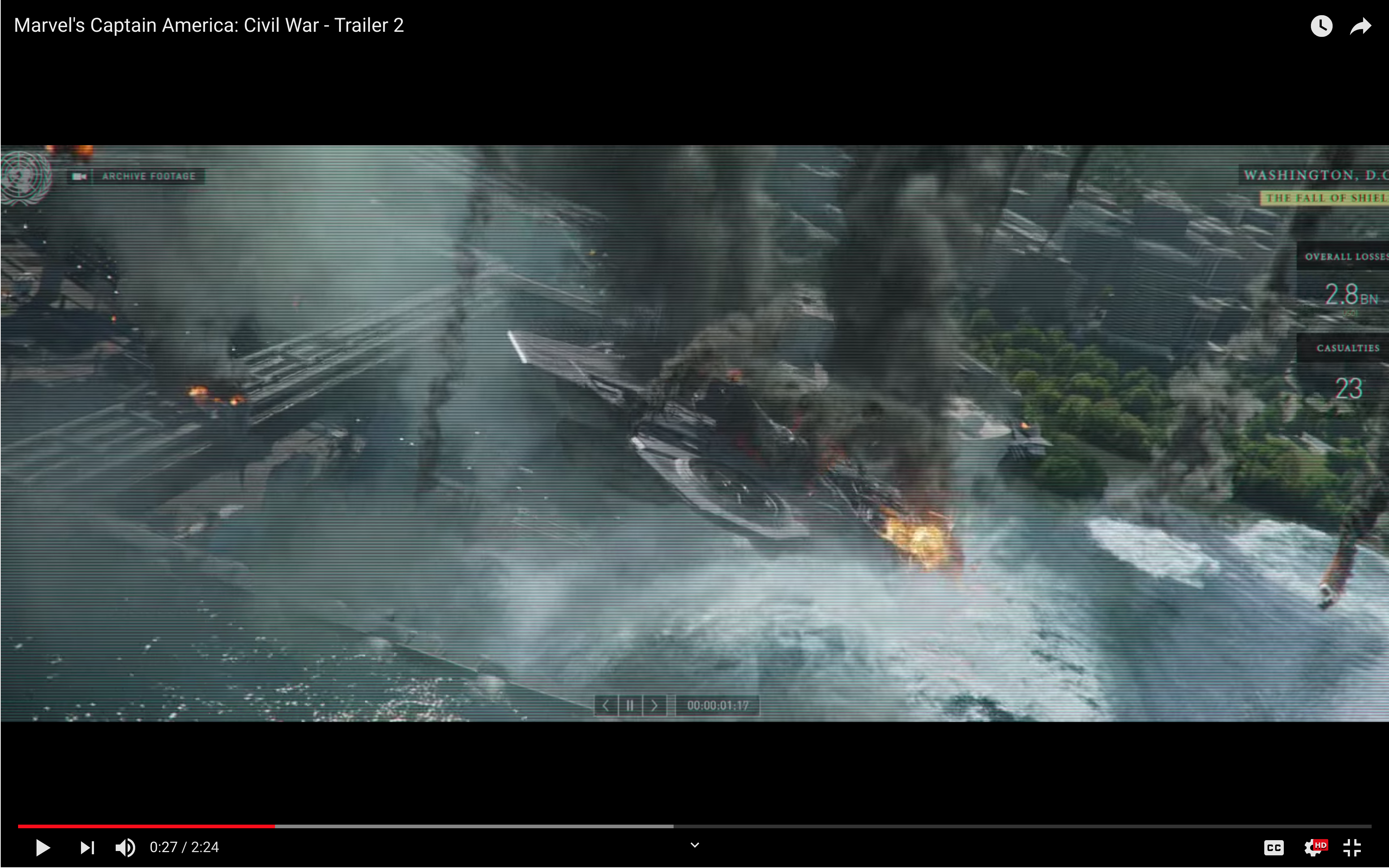

2015 - A group of teens discover secret plans of a time machine, and construct one. However, things start to get out of control. This is when blocking artifacts occur (similar to DV blocking when a tape is being FFWD).  2016 - In Captain America, archival footage features very clean and clear (digital) scan lines.

2016 - In Captain America, archival footage features very clean and clear (digital) scan lines.  2017 was a very interesting year for noise artifacts. Several trailers use them very meaningfully. In the Ghost in the Shell, ‘noise’ is more complex than contemporary compression artifacts (combining color channels, blocks, lines and some structures that are not, as far as I can see, directly referencing any compression). This must signify the ghost, existing and developing as a very complex creature inside the networks.

2017 was a very interesting year for noise artifacts. Several trailers use them very meaningfully. In the Ghost in the Shell, ‘noise’ is more complex than contemporary compression artifacts (combining color channels, blocks, lines and some structures that are not, as far as I can see, directly referencing any compression). This must signify the ghost, existing and developing as a very complex creature inside the networks. 2018 - In Annihilation, a biologist is confronted with a mysterious zone where the laws of nature (and distortion) don't apply. Here destortions are not destroying something, but they are ‘making something new’.

2018 - In Annihilation, a biologist is confronted with a mysterious zone where the laws of nature (and distortion) don't apply. Here destortions are not destroying something, but they are ‘making something new’.